@Walrus 🦭/acc For years, “put it on-chain” has been a nervous joke in Web3 circles. Everyone knows the punchline: you can’t, at least not for most of the data that makes an application feel real. The moment your project needs images, audio, video, model files, or even a chunky set of logs, a base chain becomes the wrong place to park those bytes. Fees jump, blocks bloat, and you end up treating the blockchain like a hard drive it was never meant to be. That mismatch is why “blobs” keep resurfacing in serious conversations, not as a meme but as a practical boundary line between what chains do well and what they shouldn’t be forced to do.

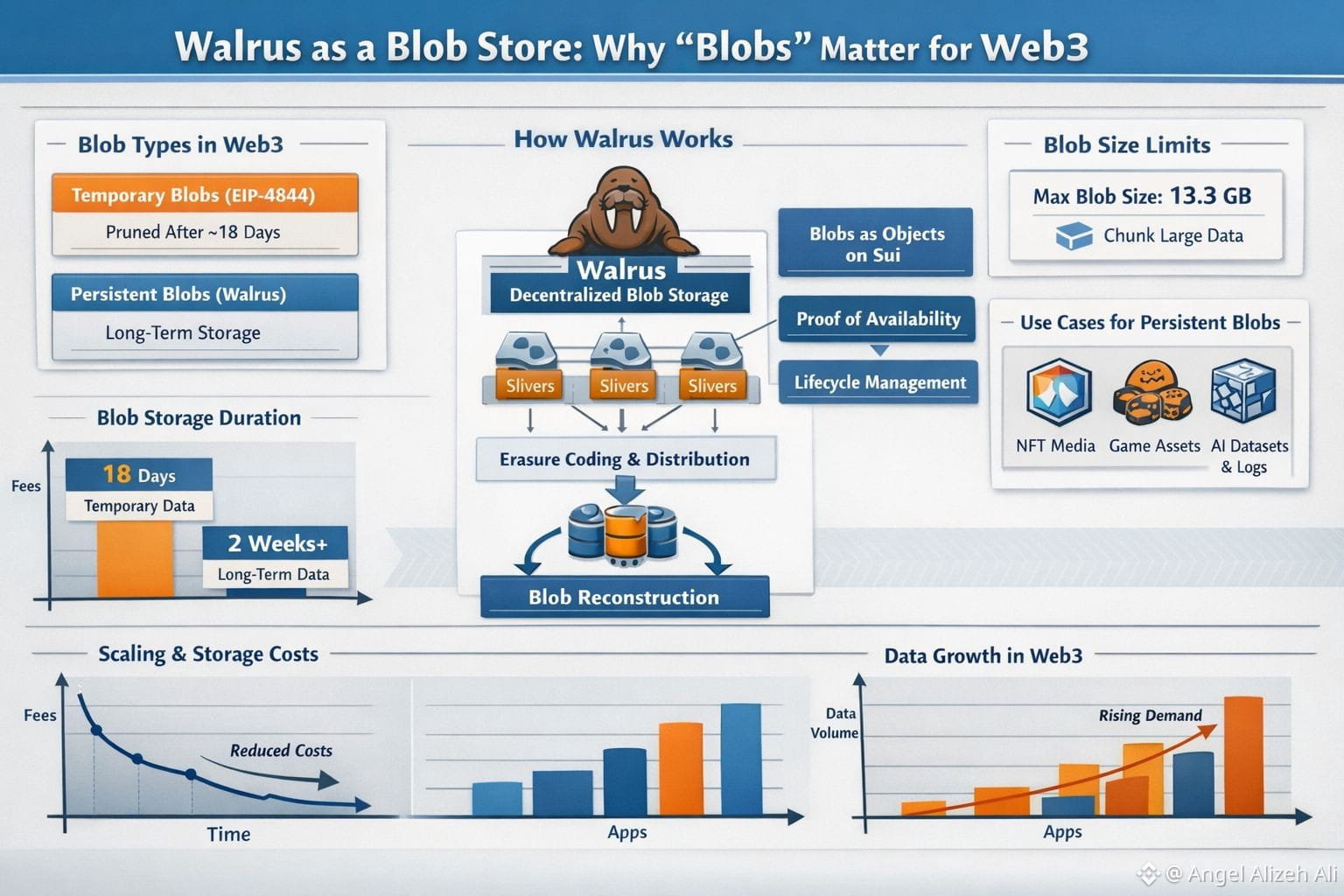

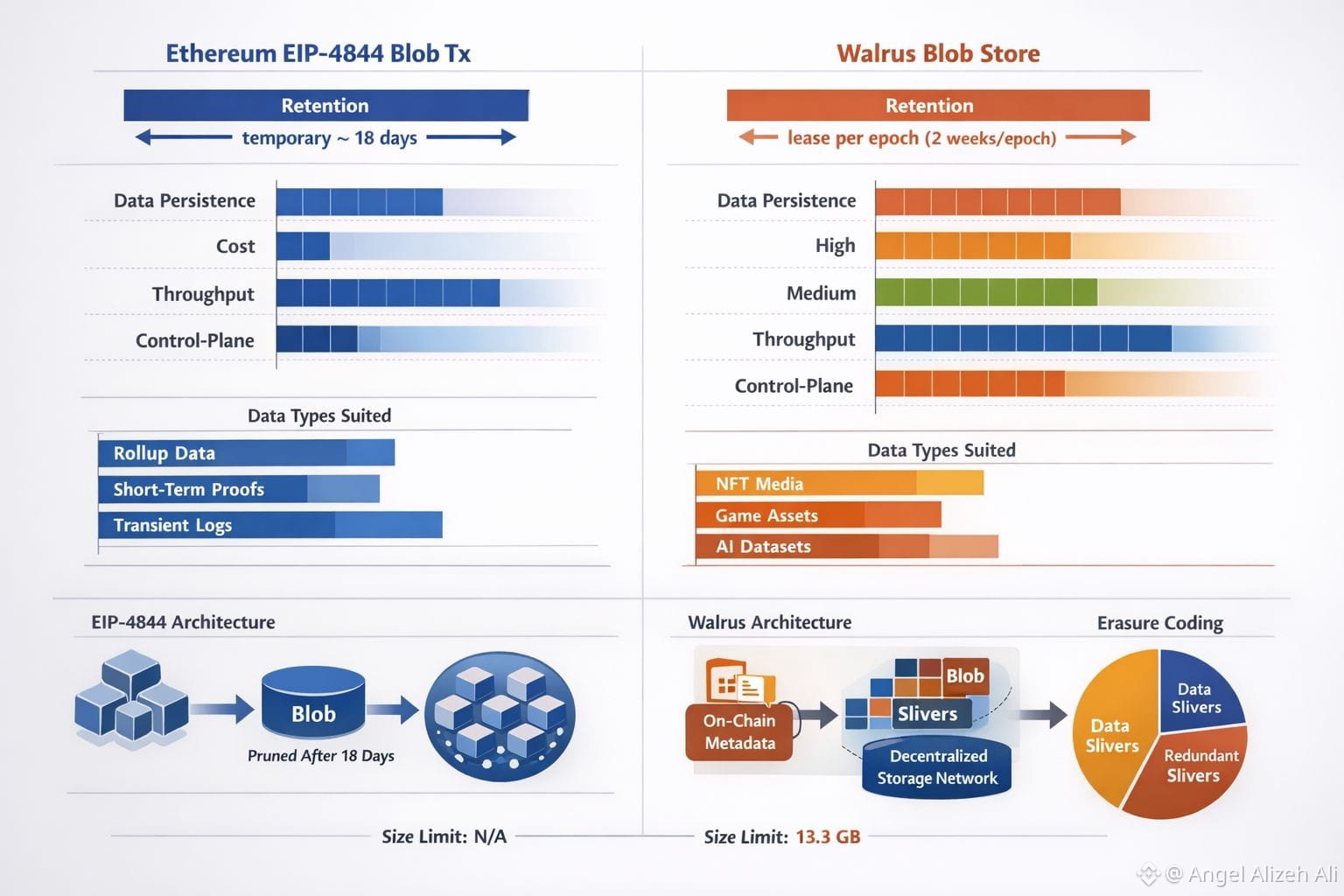

A blob is just a binary large object: a chunk of bytes stored and moved as a unit. In Web3 today, that simple idea shows up in two very different ways. Ethereum’s EIP-4844 introduced blob-carrying transactions so rollups can publish data more cheaply than permanent calldata, but with a deliberate tradeoff: blob data is temporary. The spec and explainer ecosystem are consistent on the core point—blobs are pruned after roughly 4,096 epochs, commonly summarized as about 18 days—because the network can’t afford for every scaling step to become permanent historical baggage.

That design is doing real work. After EIP-4844 went live (March 2024), blobs quickly became the normal lane for rollup data posting, and you can see the shift show up in how people talk about data availability costs and throughput as operational realities rather than research concepts. I’ve noticed the tone change in builder conversations, too. The question is no longer “can we scale?” but “what kind of data are we talking about, and how long do we actually need it to stick around?”

Because the moment you say “18 days,” a different category of needs pops up. A lot of applications want data that persists: NFT media that shouldn’t disappear, game assets that need to load next month, datasets that an AI workflow might reference repeatedly, or an audit trail you’ll want to re-check long after the launch excitement fades. The old pattern—upload somewhere centralized, pin a hash on-chain, hope the link behaves—can be fine until it isn’t. The chain can attest that a file once existed, but it can’t force anyone to keep serving it, and it can’t make storage feel like a first-class part of your app logic.

This is where Walrus earns the title “blob store” in a way that’s more literal than it sounds. Walrus was introduced by Mysten Labs as a decentralized storage and data availability protocol designed specifically to handle unstructured data blobs by encoding them into smaller pieces (“slivers”) distributed across storage nodes. The key promise is pragmatic resilience: the original blob can be reconstructed from a subset of those slivers, even when a large fraction are missing.

That’s not just a nice-to-have detail. It’s the entire point of treating blobs as a native object type rather than as an awkward attachment to a smart contract. Walrus leans on erasure coding so it doesn’t need naive full replication everywhere, and the technical paper frames this as a response to the cost and recovery inefficiencies that show up when nodes churn or partial outages are the norm rather than the exception. If you’ve ever tried to make a decentralized app feel “normal” to users—fast, predictable, and not mysteriously broken—this is the kind of engineering choice that matters more than branding.

What makes Walrus feel especially relevant to Web3, though, is how it ties storage to onchain state without pretending storage is the chain. In the Walrus documentation, storage space is represented as a resource on Sui, and stored blobs are represented as objects on Sui as well. That means smart contracts can check whether a blob is available and for how long, extend its lifetime, or optionally delete it, while the heavy bytes live in the storage network. The Walrus blog describes Sui as a control plane for metadata and for publishing an onchain proof-of-availability certificate that attests the blob is actually stored.

Those lifecycle details are where Walrus stops being an abstract “decentralized storage” idea and turns into something an application can design around. Blobs are stored for a chosen number of epochs specified at write time, and the docs explicitly note that mainnet uses an epoch duration of two weeks. In other words, storage is not a vague promise; it’s a lease with explicit time boundaries that your code can reason about. And if you need the blob to stick around longer, the client tooling supports extending blob lifetimes as long as the blob isn’t expired, with clear ownership rules around who can extend what.

Even the “boring” constraints are refreshingly explicit. The docs state a current maximum blob size of 13.3 GB, with the straightforward guidance to chunk bigger data if needed. That kind of specificity tends to be what separates a protocol you can actually build on from a concept you only talk about on panels.

So why is this trending now, beyond the usual cycle of new protocol launches? Because the industry is being forced to mature its mental model of data. Ethereum blobs made it socially acceptable to say, out loud, that some data only needs to be available temporarily for verification windows—and that optimizing for that window is a feature, not a compromise. At the same time, the apps people try to use are getting heavier: wallets that render galleries, games that stream assets, and AI-adjacent workflows that move model artifacts and provenance records around like it’s normal.

Walrus fits into that moment by focusing on the other side of the blob story: not the temporary “post it for settlement” blob, but the durable “store it, prove it’s there, and let my app manage its lifetime” blob. I’m not saying it removes the hard questions—storage networks live and die by incentives, latency, and what happens when reliability drifts over time. But it does something important: it treats blob storage as part of the core architecture instead of a side quest every team has to reinvent. That’s why Walrus feels strongly relevant to the title—and why “blobs” finally feel like they belong in the main plot, not in the footnotes.