@Walrus 🦭/acc If you’ve spent any time building or using dApps, you’ve probably felt the awkward mismatch: the “onchain” part is meant to be durable and permissionless, but the website people actually click is often just a regular bundle sitting on a cloud host. That’s not automatically a problem. It’s just a quiet dependency that becomes very loud when a frontend is taken down, a bucket is misconfigured, or a domain gets pulled at the worst possible time. Walrus Sites is one of the more practical answers I’ve seen to that specific weakness, mostly because it doesn’t try to reinvent everything. It puts the files on Walrus, and keeps the ownership and site metadata on Sui, so the right to update a site looks more like an onchain asset than a login to a hosting dashboard.

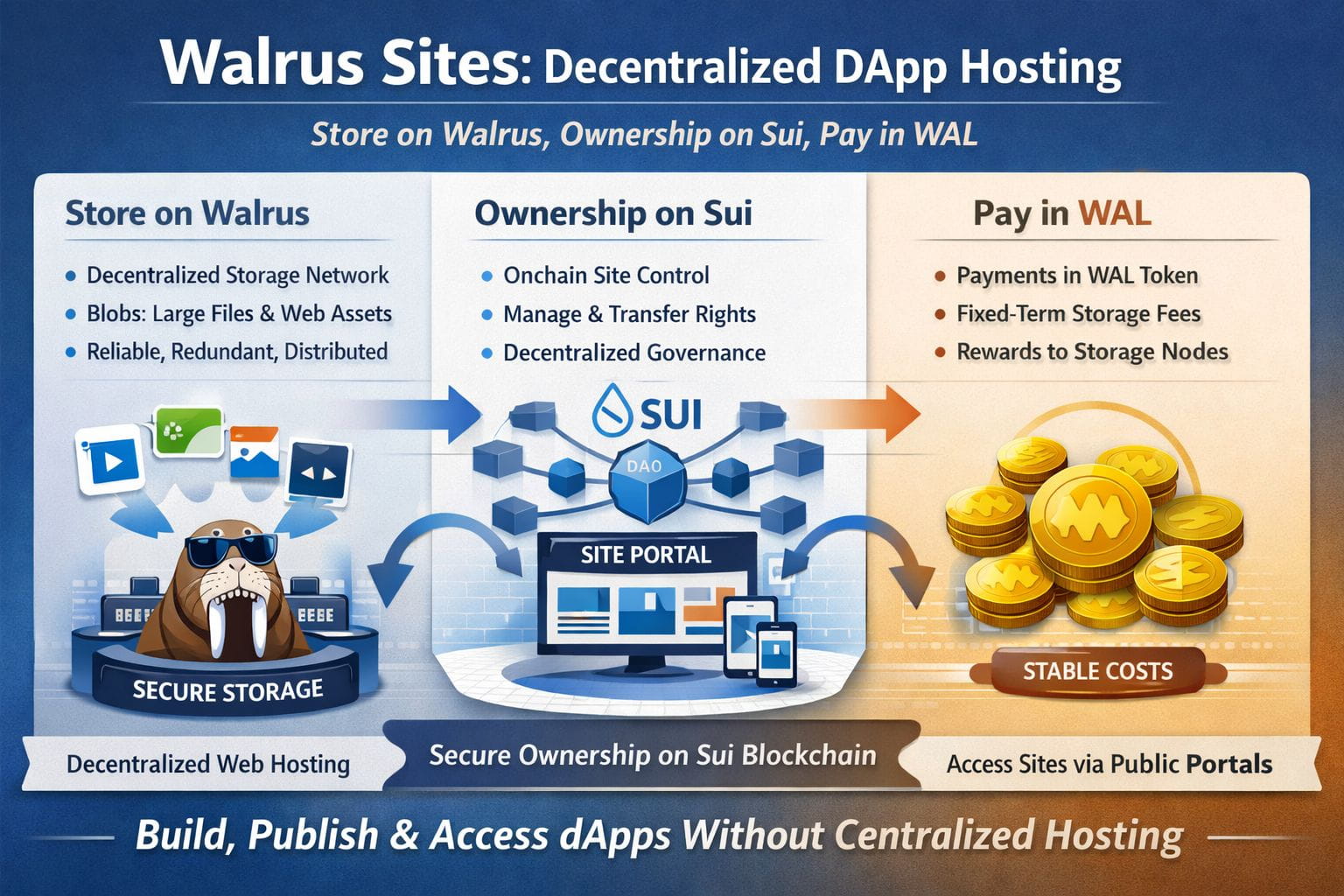

To make the title feel real rather than poetic, it helps to be specific about what Walrus is. Walrus is a decentralized storage protocol focused on storing large, unstructured files—images, video, datasets, and the kind of “web stuff” that ends up as static assets—on a network of independent storage nodes, with an emphasis on availability even when some participants behave badly or fail. In Walrus language, those stored chunks are “blobs,” and the system is designed so apps can treat storage less like a best-effort file cabinet and more like a thing with rules and a lifecycle.

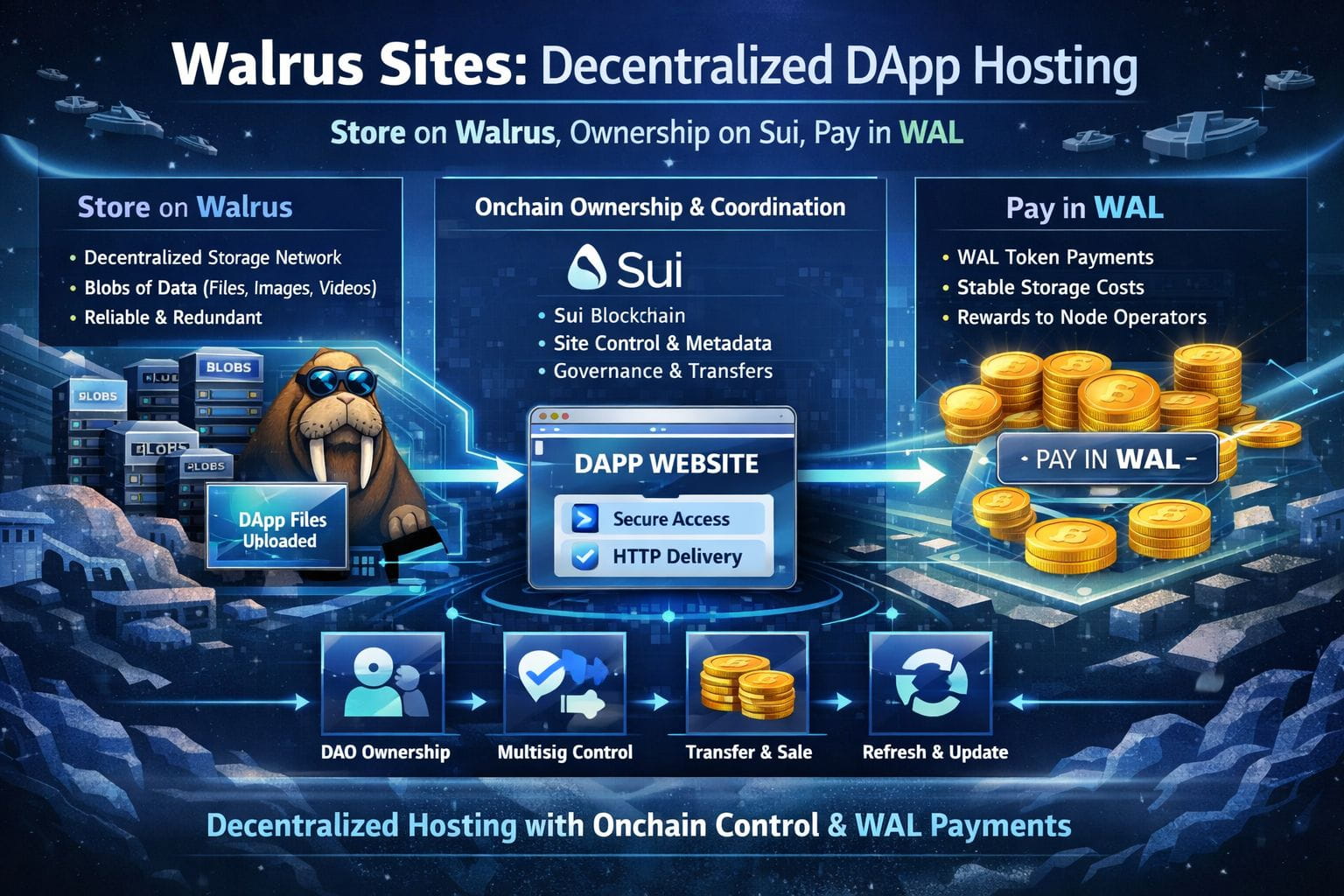

That lifecycle piece is where Sui matters. Walrus uses Sui as the coordination and ownership layer: who controls a piece of storage, how long data should persist, and what it means to extend, delete, or transfer it. In practice, Walrus represents stored data and storage-related rights in a way Sui contracts can read and act on, which opens up a bunch of plain, non-magical workflows: a DAO can own a site, a multisig can control updates, a game can programmatically refresh assets, or a marketplace can transfer a storefront as part of a sale. This is the “ownership on Sui” part of the title, and it’s not a marketing flourish—it’s the mechanism that lets a website behave like a governed digital object instead of an admin panel.

Walrus Sites is the visible, browser-facing version of that idea. You build a normal site (the docs lean toward static outputs), publish the resulting files to Walrus, and get back identifiers that can be resolved and served to users through a portal. The documentation points to a public portal run for general access, and it’s clear that “portal” is a general term: anyone can run one, including locally, and known portals can be listed openly. This is an important nuance that tends to get lost. The portal is a point of convenience, not the source of truth. It fetches metadata from Sui and content from Walrus, then serves it over HTTP so a normal browser can load the site without wallets or special tooling.

Then there’s the third clause in the title—“Pay in WAL”—which is where projects like this either become viable or quietly fade. Walrus uses WAL as the payment token for storage. Users pay up front to store data for a fixed time, and that payment is distributed over time to storage nodes and stakers who secure and operate the network. Walrus also describes a design goal that storage costs should remain relatively stable in fiat terms, so you’re not constantly recalculating budgets based on token volatility. I’m cautiously optimistic about that framing, because “stable pricing” is easy to promise and hard to maintain, but at least Walrus is explicit about the intent and the mechanics rather than hand-waving it away.

So why does this feel more relevant now than earlier “decentralized web” waves? Partly because Walrus isn’t speaking from a perpetual testnet future tense anymore. The March 27, 2025 mainnet launch was the moment it stopped being a “someday” project and started being a thing developers could test, break, and build on. Once a system is live, developers start caring about boring details—tooling, reliability, publishing flows, and whether the thing breaks when real users show up. Walrus Sites, as a concrete “here’s a website, it loads” demo of the storage layer, benefits from that shift.

None of this makes frontends automatically safe. A portal can still track traffic or rate-limit requests. A site can still ship insecure JavaScript. And there’s a broader question hiding in the background: how much decentralization does a normal user actually need before it’s worth the trade-offs? But I do think Walrus Sites lands on a sensible middle ground. It doesn’t pretend the web is going to stop using HTTP tomorrow. It just tries to make the most brittle part—the hosted files and the authority to change them—more durable, more transparent, and easier to govern with the same onchain tools people already trust for value. That’s not a revolution. It’s something rarer in this space: a credible improvement.