Most technical discussions about storage start with performance numbers or cost graphs but the real problem usually appears much later when no one is looking closely anymore. Systems do not struggle because they store too much data they struggle because they do not understand which data should still matter. Over time platforms quietly carry old assumptions forward and those assumptions begin shaping decisions they were never meant to influence. This is where products start to feel heavy even when traffic is normal and infrastructure looks healthy.

In early development everything feels justified. Teams move fast temporary shortcuts make sense and keeping extra data feels safe. The system is young and everyone remembers why things exist. At this stage nothing feels dangerous because context is fresh. But systems do not stay small. Teams change users change goals change markets change. What does not change is the data that was created under very different conditions.

As platforms grow that early data keeps participating in live logic. It influences routing prioritization permissions and behavior long after its original purpose has expired. No single bug appears. Nothing crashes. Instead the system becomes harder to reason about. Engineers hesitate before making changes because hidden dependencies might break. Operations teams rely more on monitoring because behavior is less predictable. Every new feature feels riskier than the last.

This is not a technical failure. It is a design gap. Most systems are built to remember but not to forget. They store information indefinitely but never ask whether that information should still have authority. Existence and influence are treated as the same thing. As long as data exists it continues shaping outcomes.

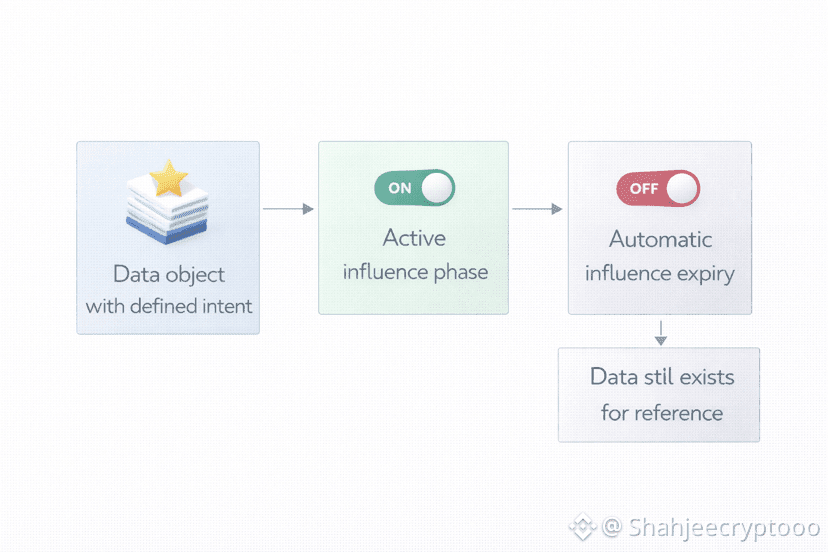

This is where Walrus introduces a different way of thinking. Walrus separates data existence from data influence. Data can remain stored for records auditing or reference while its ability to affect current behavior can end. This one distinction removes a huge amount of hidden complexity. Old context stops quietly controlling new logic.

In Walrus every data object carries clear intent. It exists for a reason and that reason is enforced by the protocol. Ownership is explicit. Responsibility is assigned. And most importantly influence is time scoped. When that scope ends the system does not rely on humans to remember cleanup. The influence simply stops.

This design changes how teams work. Developers stop writing defensive code to protect against unknown historical states. They can trust that outdated data will not interfere with current logic. Operations teams see fewer strange edge cases because the system behavior is aligned with present rules not legacy ones. Product teams gain confidence because changes affect what is active now not everything that ever existed.

Another important effect appears in how systems evolve. Platforms without enforced intent become afraid of change. Every update risks triggering old logic paths that no one fully understands. Over time innovation slows not because ideas run out but because uncertainty grows. Walrus reduces this uncertainty by narrowing the surface area of active influence. Systems know exactly what is allowed to shape decisions at any moment.

Users benefit from this in subtle ways. Interfaces feel more consistent. Behavior matches expectations. Features do not behave differently depending on invisible historical states. Trust grows not through promises but through predictable outcomes. People stop questioning results because the platform behaves the same way today as it did yesterday for the same reason.

Cost control also improves naturally. When influence expires unnecessary processing drops. Lookups become simpler. Storage usage becomes intentional instead of accidental. Teams no longer pay the price of forgotten data constantly participating in live workflows.

What makes Walrus different is that this is not an add on or a policy layer. These rules live at the protocol level. They are enforced automatically. No manual cleanup scripts. No reliance on tribal knowledge. The system explains itself through structure.

This approach prepares platforms for long term growth. Most serious failures do not happen when systems are new. They happen years later when original builders are gone and context has faded. By enforcing intent ownership and time from the start Walrus protects systems from that future decay.

In the end strong platforms are not defined by how much they store but by how carefully they decide what should still matter. Walrus is built for teams that want their systems to age well not just scale fast.