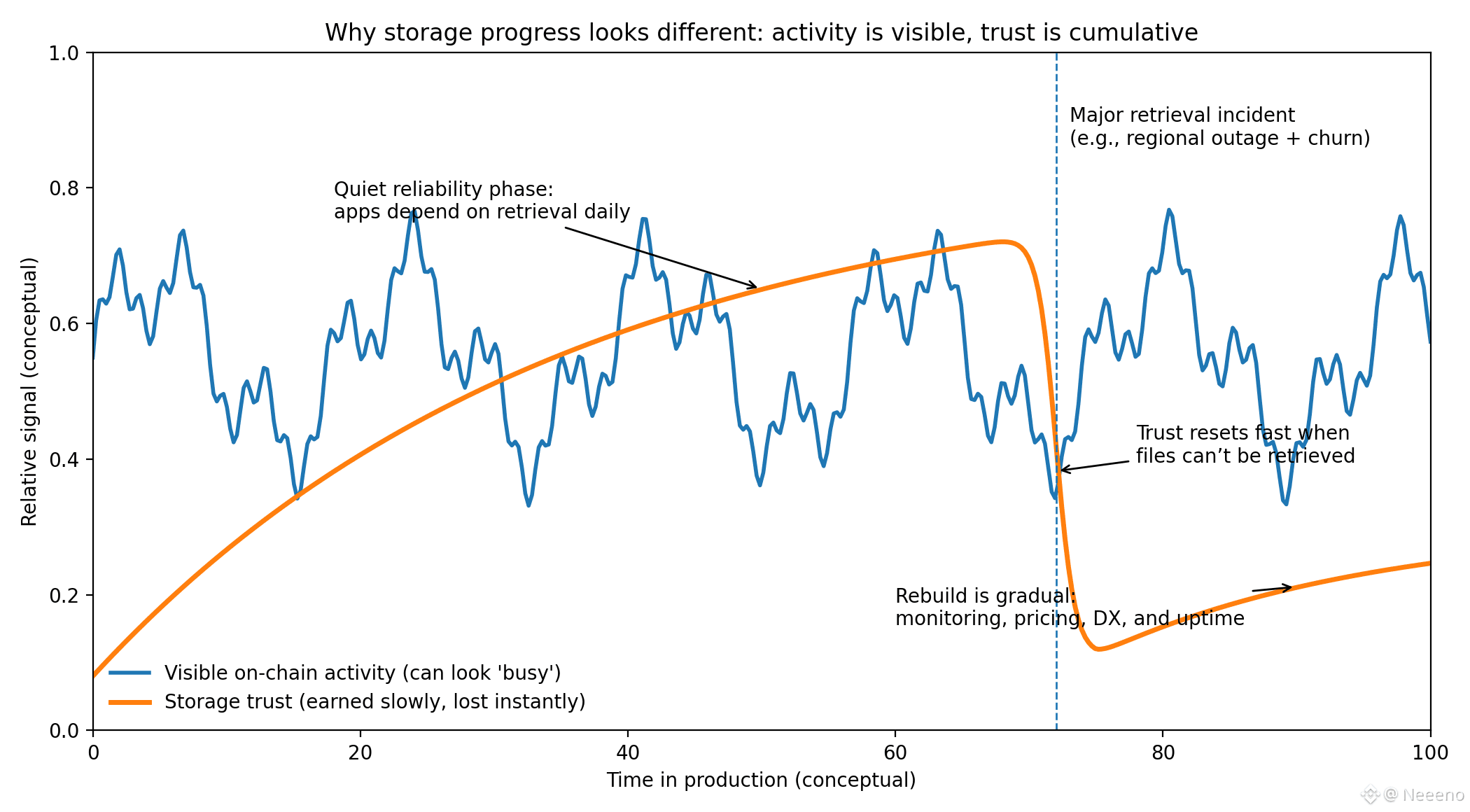

@Walrus 🦭/acc Crypto systems tend to celebrate what they can count. TPS, daily active addresses, fees, and new contracts can tell you something, but they can also mislead. It’s easy to mistake “a lot is happening” for “real progress is being made.”Storage earns trust on a different timetable. A compute system can look busy for weeks and still fail the first time a real product depends on it under pressure. A storage system becomes “real” only when applications lean on it day after day, when retrieval keeps working through the messy conditions teams try not to think about, and when the operational story is boring enough that people stop talking about it.That’s the context for Walrus’s approach. Walrus is basically a decentralized storage network for big “blobs” of data, designed to make retrieval dependable. It targets content- and data-heavy apps where files are big, come in constantly, or matter too much to risk. The message is clear: storage isn’t a bolt-on—it’s foundational, because the downside of messing it up is far greater than people expect. Walrus also frames itself as a foundation for “data markets” in an AI-shaped economy, where data and the artifacts derived from it can be controlled, accessed, and paid for in a more native way. That framing is explicit in its public materials, which emphasize data as an asset and highlight AI-agent use cases alongside more familiar content and media workloads.

It is worth lingering on why storage is a harder promise than compute. Compute problems are usually local and fixable: you rerun the job, swap the machine, and an outage turns into a report and a patch. Storage problems feel heavier because lost data can be gone forever.You can fake compute activity by spamming cheap calls, but you can’t fake years of reliable retrieval. A serious team does not care that a storage network can accept uploads today if they are not confident those uploads will still be retrievable next quarter, next year, and after the original operators have moved on. That is why trust in storage is earned slowly and lost instantly. It is also why adoption tends to arrive later than the narratives suggest. The switching costs are high, and the failure mode is brutal: you don’t just break an app, you break its memory.

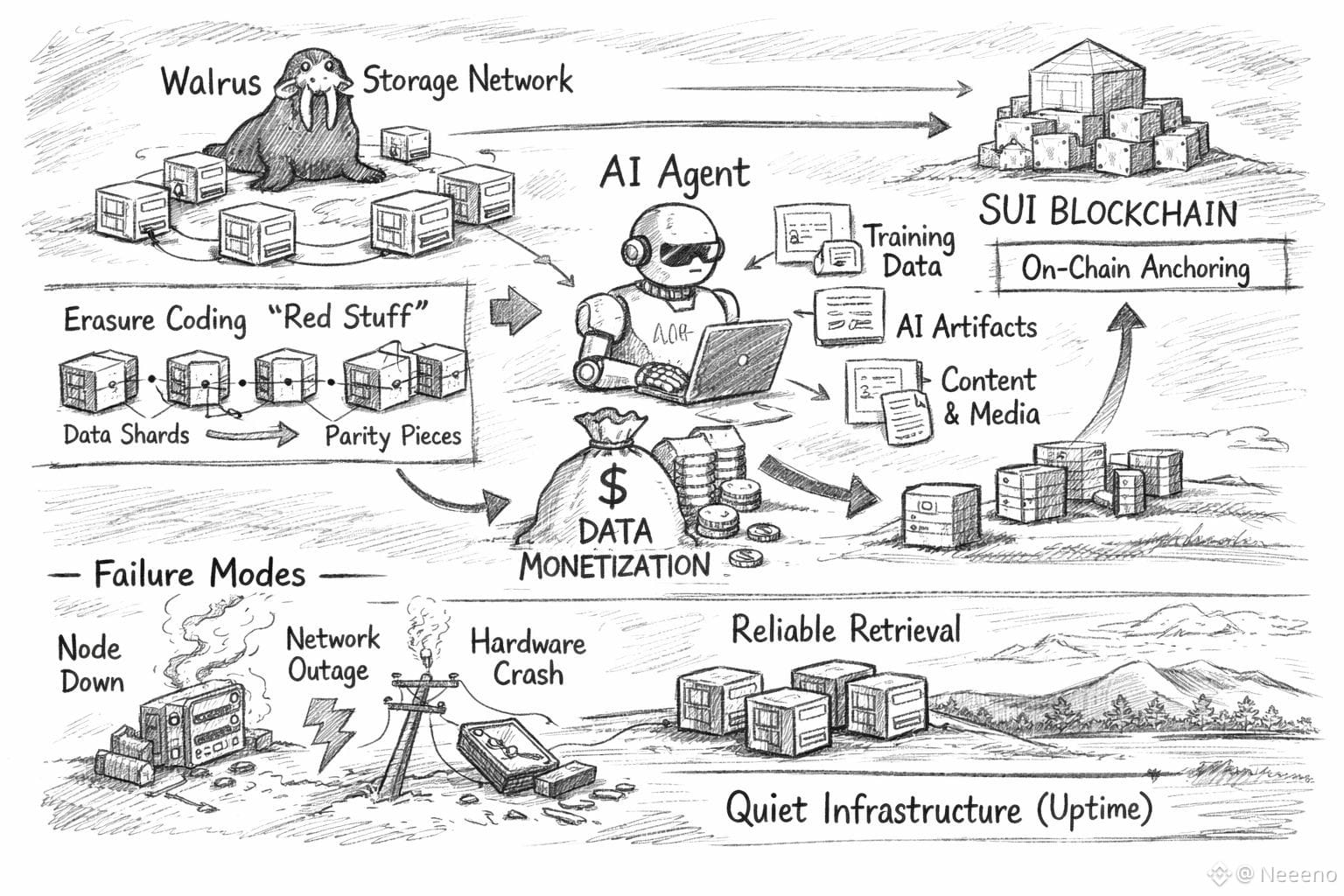

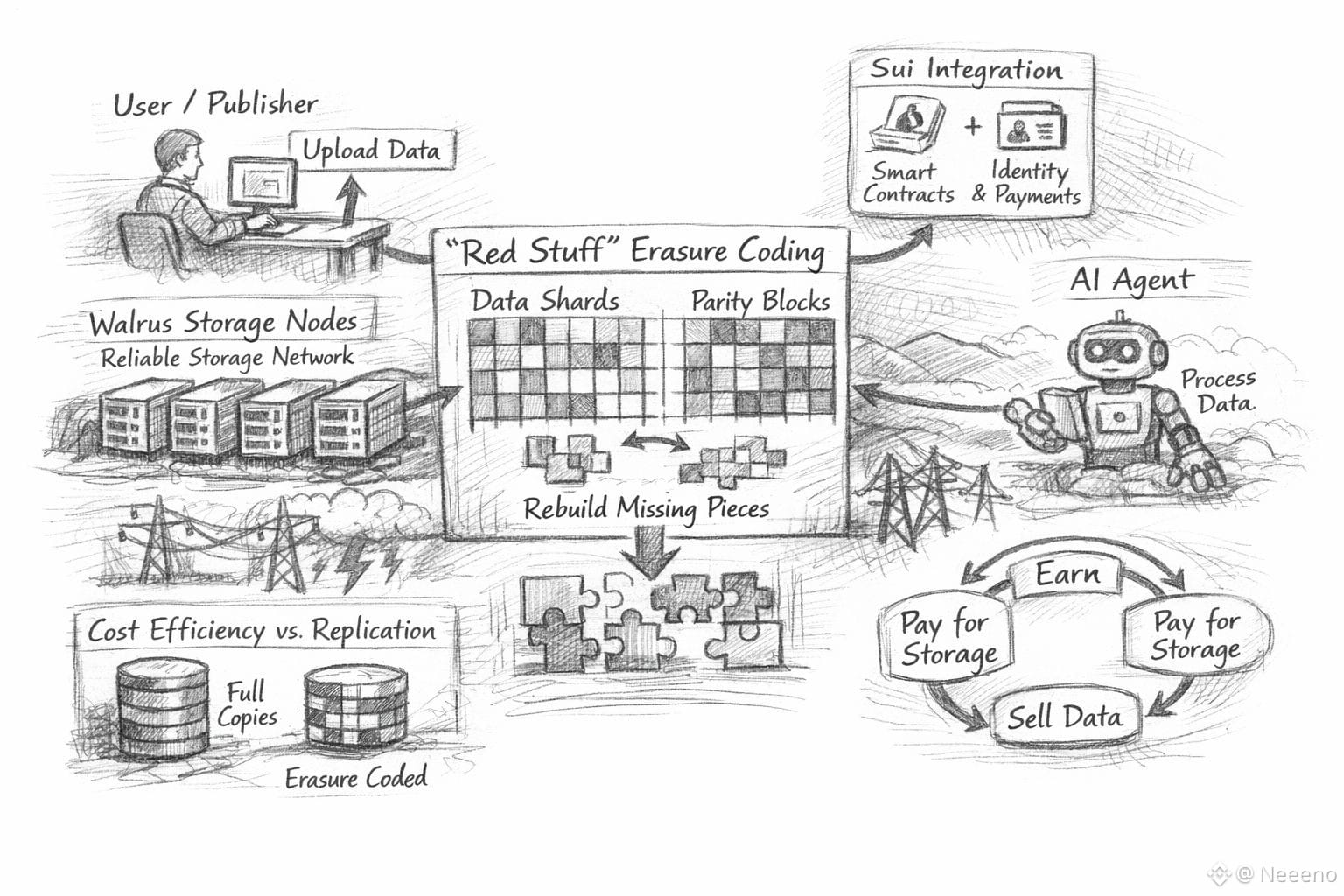

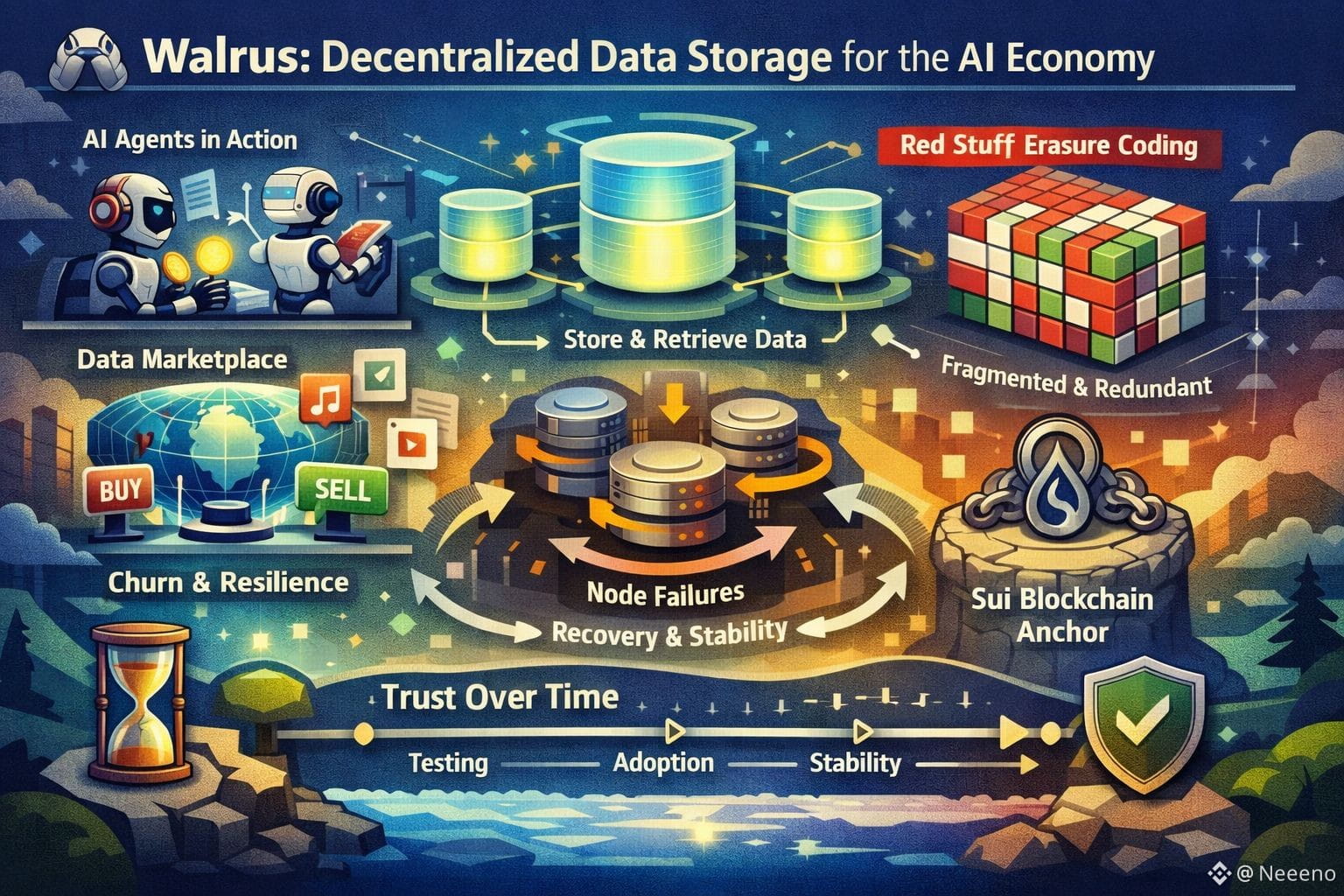

Walrus’s technical story is built around resilience and efficiency under those conditions. At a high level, it relies on erasure coding—specifically an approach it calls “Red Stuff”—to split data into pieces and add redundancy so the original blob can be reconstructed even if some pieces are missing. The intuition is simple: instead of making many full copies of the same file across many machines, you break the file into fragments and store a structured set of extra fragments that can “fill in the gaps” when the world behaves badly. Walrus describes Red Stuff as a two-dimensional erasure coding protocol designed to keep availability high while reducing the storage overhead that comes from pure replication, and to support recovery when nodes churn in and out.

This matters because the baseline for decentralized storage is not a clean lab environment; it is everyday chaos. Operators churn. Hardware fails in uninteresting ways: disks degrade, power supplies die, networks flap. Connectivity is spotty at the edge and merely “good enough” in many places teams actually deploy. Regional outages happen, sometimes because of natural events, sometimes because of upstream providers, sometimes for reasons no one can fully explain in the moment. A storage network that assumes stable participation is a storage network that will disappoint you precisely when you need it. The Walrus research and documentation put churn and recovery costs near the center of the design problem, which is a quiet signal of seriousness: it is easier to demo a happy-path upload than it is to engineer a system that treats churn as normal.

The efficiency angle is not just about saving money in the abstract; it is about making real products feasible.Replication-based storage is basically: duplicate the entire blob many times, then rely on the fact that at least a few copies won’t disappear. It’s simple, but it gets pricey when usage grows. Overhead isn’t an “optional” metric in storage—it controls what’s practical: keeping media online for an app, shipping game updates regularly, or archiving massive data without paying to re-upload it over and over.Retrieval performance is equally decisive. If developers have to choose between decentralization and user experience, most will quietly choose user experience, especially when their reputations and SLAs are on the line. Walrus’s public descriptions of Red Stuff focus on reducing the traditional trade-offs: lowering overhead relative to full replication while keeping recovery lightweight enough that churn doesn’t erase the savings.

This is also where the “AI agents as economic actors” framing becomes more than a slogan, if it is taken seriously. The practical bottleneck for agentic systems is not only reasoning or execution; it is state, memory, and provenance. Agents produce artifacts: intermediate datasets, model outputs, logs, traces, tool results, and the slow accretion of context that makes them useful over time. If those artifacts live in centralized buckets, then the agent economy inherits the same brittle assumptions as Web2 infrastructure: a single admin can revoke access, pricing can change without warning, accounts can be frozen, and the continuity of the agent’s “life” depends on a vendor relationship. Walrus argues for a world where these artifacts are stored in a decentralized layer and can be retrieved and verified reliably, creating the conditions for data to be shared, permissioned, and monetized in a more native way. Its own positioning emphasizes open data marketplaces and agent-oriented workflows, and it has highlighted agent projects as early adopters.

Monetization, in this context, is less about turning every byte into a speculative commodity and more about making data access legible and enforceable. For an AI agent to become an economic actor, it needs a way to pay for storage, pay for retrieval, and potentially earn from the artifacts it produces—while preserving enough control that the “asset” isn’t instantly copied and stripped of value. The details of market design are still an open field across the industry, but storage is one of the few layers where the constraints force clarity: someone pays for persistence; someone pays for serving; someone bears the operational risk. Walrus’s token and payment design is presented as an attempt to make storage costs predictable in practice, including a mechanism described as keeping costs stable in fiat terms over a fixed storage period, which is the kind of unglamorous decision infra teams tend to appreciate.

Walrus is also closely associated with the Sui ecosystem, and that anchoring is not just branding. When a storage layer is integrated with an execution layer, a few practical frictions get smoother. Payments become composable instead of off to the side. Identity and access patterns can be expressed with the same primitives developers already use for apps. References to stored blobs can live on-chain in a way that is easier to verify and automate. In the Walrus academic paper, the authors explicitly describe the system as combining the Red Stuff encoding approach with the Sui blockchain, suggesting a design where the chain plays a coordination and verification role while the storage network does the heavy lifting on data. That kind of coupling can be a real advantage for developer experience, if it stays simple and avoids forcing teams into unusual operational gymnastics.

A grounded usage example helps keep this from drifting into abstractions. Imagine a small team building a media-heavy application—say, a product that lets users publish long-form content with embedded audio, images, and downloadable files. In a centralized setup, the team uses a cloud bucket and a CDN and hopes they never have to migrate. In a decentralized setup that actually aims to be production infrastructure, the team wants two things that sound boring but are existential: predictable retrieval and predictable costs. They do not want to explain to users why an old post is missing an attachment because a node disappeared, or why a minor spike in usage caused storage bills to explode. Walrus is pitching itself as a storage layer where the application can upload large blobs, reference them reliably, and keep serving them even as individual storage operators come and go, because the system assumes that kind of churn will happen.

All of this collapses, however, if operational trust is not earned in the way infra teams require. Teams don’t migrate critical data because a protocol has an interesting paper; they migrate when the day-to-day story feels safe. That usually means clear monitoring and debugging surfaces, stable SDKs, and a pricing model that doesn’t require constant treasury management to avoid surprises. It means the failure modes are well understood and the recovery paths are not heroic. It also means the social layer matters: someone has to be on call, someone has to publish postmortems, someone has to keep the developer experience coherent as the system evolves. Walrus’s own updates emphasize product-level work like developer tooling and making uploads reliable even under spotty mobile connections, which speaks to this operational reality more than many glossy narratives do.

The balanced view is that storage adoption is slow for good reasons. The switching costs are high because data has gravity, and because the penalties for mistakes are permanent in a way compute outages often are not.Even if a storage system works well on paper, most teams will be careful. They’ll run it alongside their current setup, push it hard to see how it behaves under stress, and only then move the truly important data.Walrus succeeds if it becomes quiet infrastructure—noticed less as a protocol and more as a reliable assumption. If the network can keep doing the uncelebrated work of retaining and serving large blobs through churn, outages, and ordinary dysfunction, then the more ambitious vision—agents that store, retrieve, and monetize artifacts as part of real economic workflows—has a credible foundation to build on. If it can’t, no amount of on-chain activity will compensate, because storage is one of the few layers where the truth arrives not in announcements, but in the long, uneventful stretch where nothing goes wrong.