If Part 1 framed weak tokenomics as a structural issue across the market, Part 2 focuses on a more nuanced reality: Tokenomics rarely kill a project on their own. What truly pressures price is vesting — when it arrives at the wrong time.

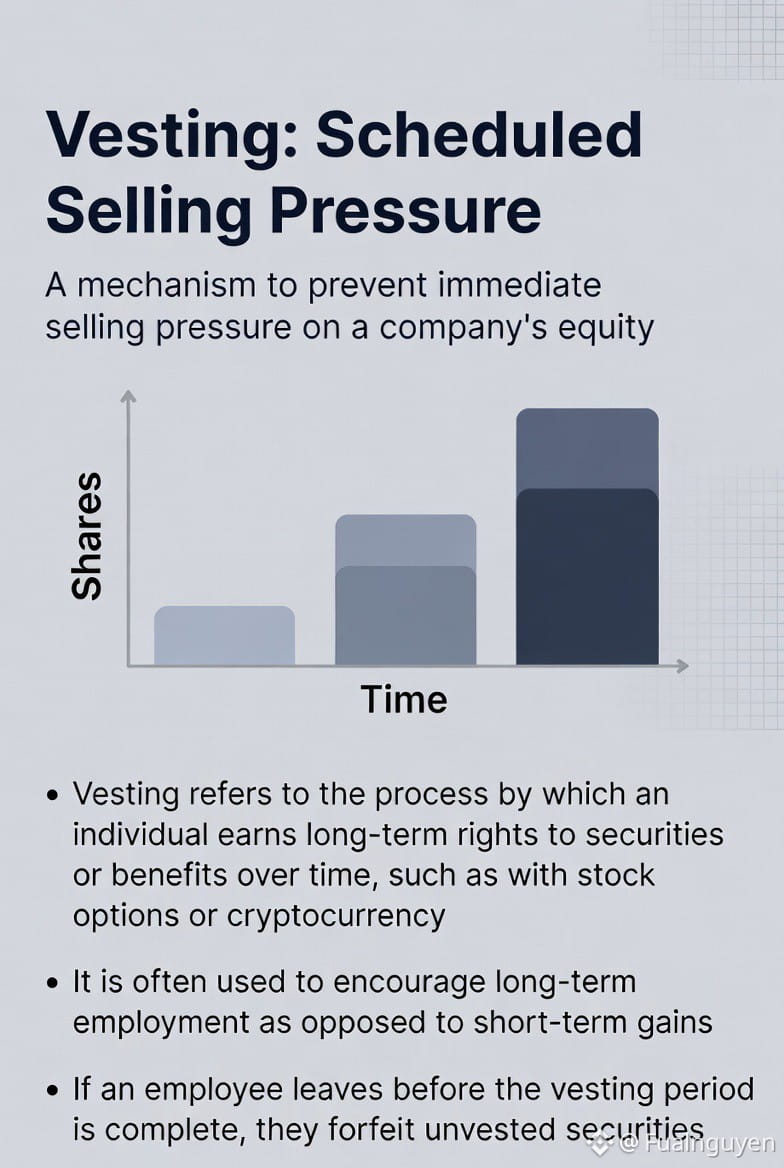

1. Vesting: Scheduled Selling Pressure

Markets can tolerate many imperfections: an unfinished product, an unclear narrative, a lack of immediate revenue. But markets never ignore supply that is guaranteed to hit the market.

By nature, vesting represents:

Identified future supply

Sellers with near-zero cost basis

Selling decisions detached from market sentiment

In a low-liquidity environment, vesting stops being a future risk and becomes present selling pressure.

2. The Common Mistake: Evaluating Vesting in an Ideal Market

Many tokenomics analyses implicitly assume:

“The market will always have enough capital to absorb new supply.”

Reality tells a different story:

Bull markets are not continuous

Capital flows are cyclical and selective

Not every project benefits from the same narrative

Vesting works well in bull markets, but in sideways or bearish conditions, it can become a multi-quarter drag on price.

3. Who Is Vesting Matters More Than How Much

Not all unlocked supply is equal:

Team / Founders: selling for risk diversification - understandable

Early VCs: selling to meet IRR targets and fund lifecycles - almost inevitable

Incentives / Rewards: selling due to lack of holding incentives

A token with modest vesting can still underperform if supply ends up in the wrong hands, while a token with larger vesting may fare better if:

Lockups are long

Unlocks are gradual

Real demand exists to absorb supply

4. Case Study: Arbitrum (ARB) — Sound Tokenomics, Persistent Vesting Pressure

Arbitrum offers a clear real-world example.

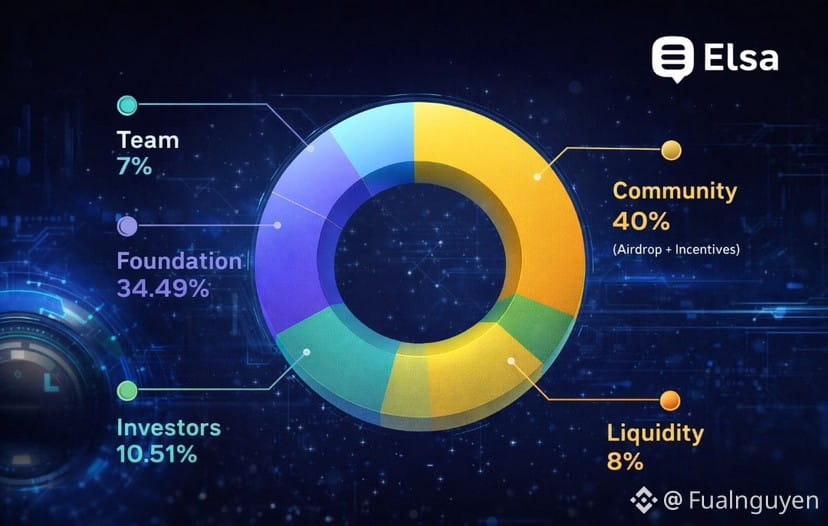

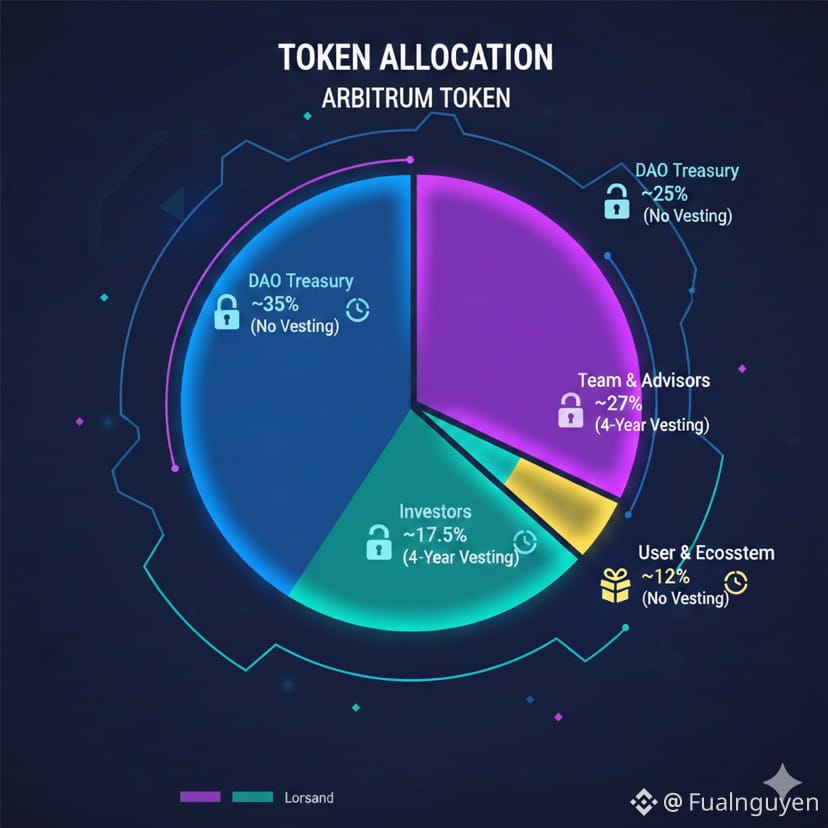

Tokenomics on Paper

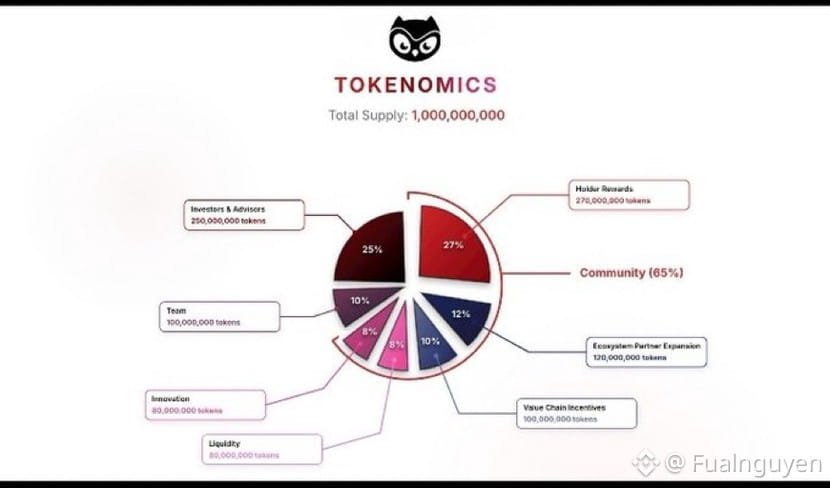

Total supply: 10 billion ARB

Allocation follows industry standards:

DAO Treasury

Team & Advisors (long-term vesting)

Investors (long-term vesting)

Airdrop & ecosystem distribution

From a design perspective, ARB does not suffer from poor tokenomics. Vesting is transparent and structured to avoid sudden supply shocks.

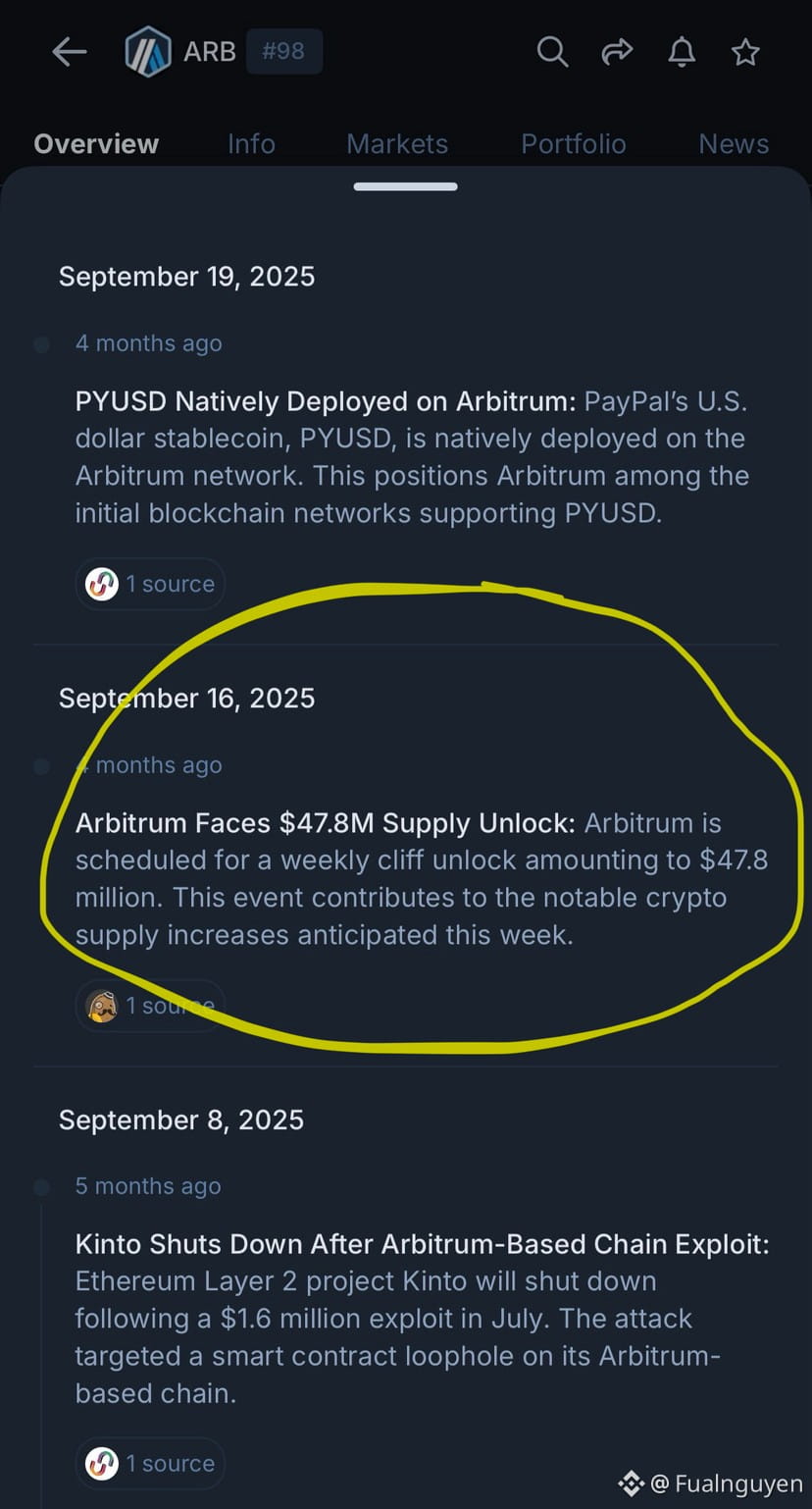

The Real Issue: Cliff Expiry in a Weak Liquidity Environment

After the one-year cliff ended, ARB entered a phase of:

Large initial unlocks

Followed by steady monthly releases over several years

The first major unlock led to:

Increased exchange inflows

Visible selling from insiders and early investors

Short-term negative price reactions

Not because the tokenomics were flawed, but because: New supply entered the market when there was insufficient opposing liquidity.

A Second Constraint: Utility That Doesn’t Absorb Supply

ARB functions primarily as a governance token:

Network usage continues to grow

On-chain activity improves

But demand for holding ARB does not scale proportionally with network adoption

As monthly supply unlocks continue, and demand remains largely speculative, sustained upside becomes difficult.

5. Good Tokenomics Can Still Fail When Timing Is Wrong

The Arbitrum case highlights a broader lesson:

Solid token design does not guarantee strong price performance

Transparent vesting does not eliminate selling pressure

Timing matters as much as structure

Correct tokenomics + poor timing = continued price pressure.

6. Investor Takeaways for 2024–2026

In the current cycle, tokenomics are no longer tools for finding upside — they are tools for managing downside risk.

Instead of asking:

“Is the vesting schedule heavy?”

Ask:

Who receives the unlocked tokens?

Do they have incentives to hold?

What capital is positioned to absorb that supply?

Vesting is not inherently bad. Tokenomics are not the enemy.

But in a liquidity-selective market, vesting at the wrong time can suppress price for multiple quarters — even for fundamentally sound projects like Arbitrum.