@Vanarchain Major game studios don’t choose infrastructure because it sounds visionary in a deck. They choose it because shipping a live game is an exercise in controlled fear. Fear of breaking a login flow that took years to optimize. Fear of an update that changes retention curves overnight. Fear of a support queue that explodes because a payment failed in a way nobody can explain. When studios look at Vanar for high-speed onboarding, what they’re really asking is a quieter question: can this system let us move fast without turning every release into a gamble?

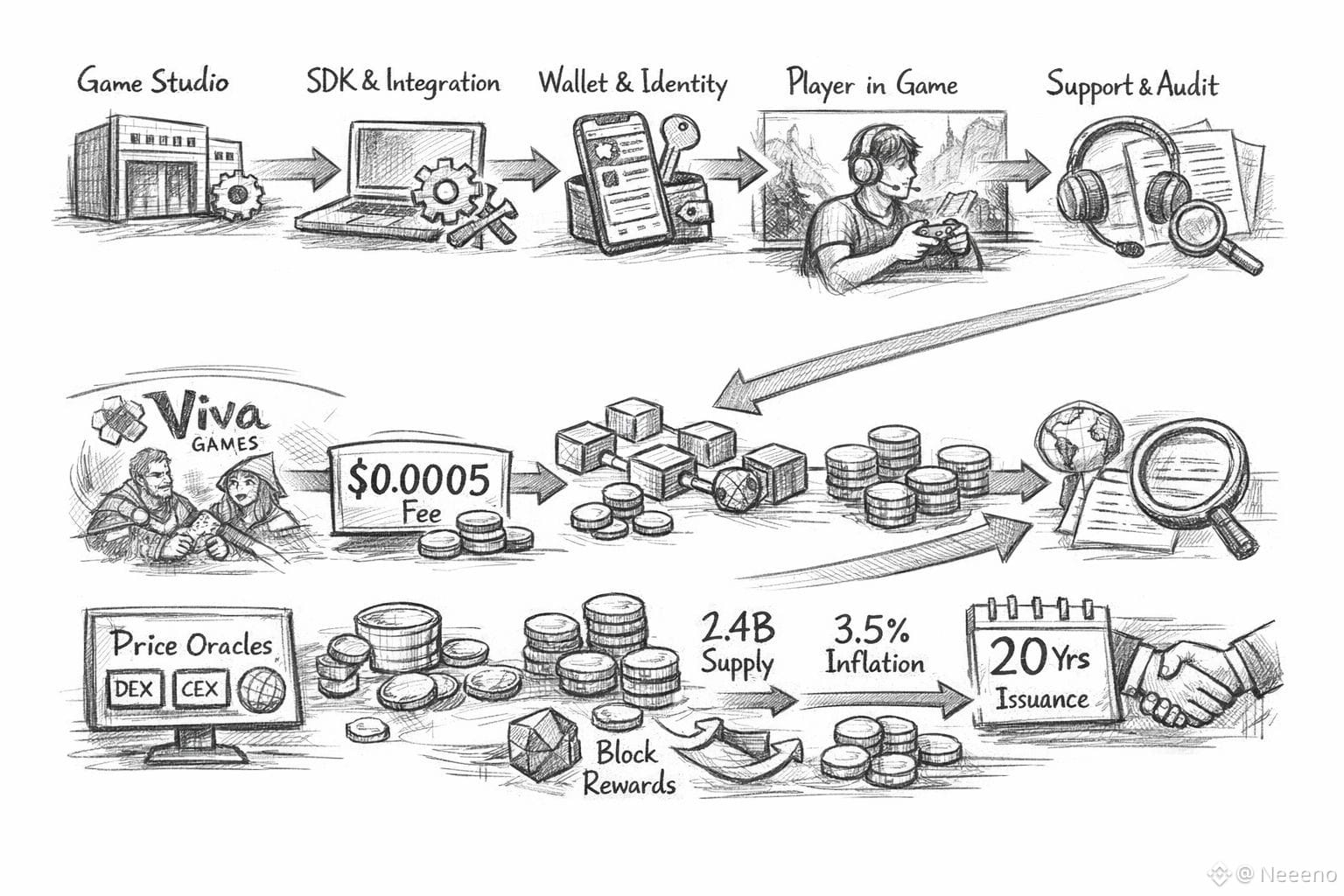

Vanar’s appeal to game teams starts with something that’s easy to underestimate from the outside: time-to-first-working-build. In a studio, momentum is a fragile resource. Producers want something playable in days, not a “blockchain sprint” that drains months and still leaves basic flows feeling awkward. Vanar has built its public story around reducing friction for teams that already know how to ship, by letting them keep their familiar development habits while adding what they need for ownership and on-chain state without rewriting the whole game around crypto. That sounds mundane, but for a studio trying to onboard millions, “mundane” is often the highest compliment.

The reason onboarding speed matters so much in gaming is that the first five minutes are the product. Traditional game teams have spent a decade learning that every extra tap, every confusing permission, every unfamiliar concept costs them players forever. If a system forces new accounts, new mental models, or new failure modes right at the start, the studio doesn’t just lose users—it loses confidence. That confidence is emotional, not academic. Teams stop experimenting, features get cut, and the project quietly retreats back to the safe center. Vanar’s positioning toward gaming has consistently emphasized “normal-feeling” entry—getting players into the experience quickly, then letting deeper ownership and economic layers show up only when the player is ready.

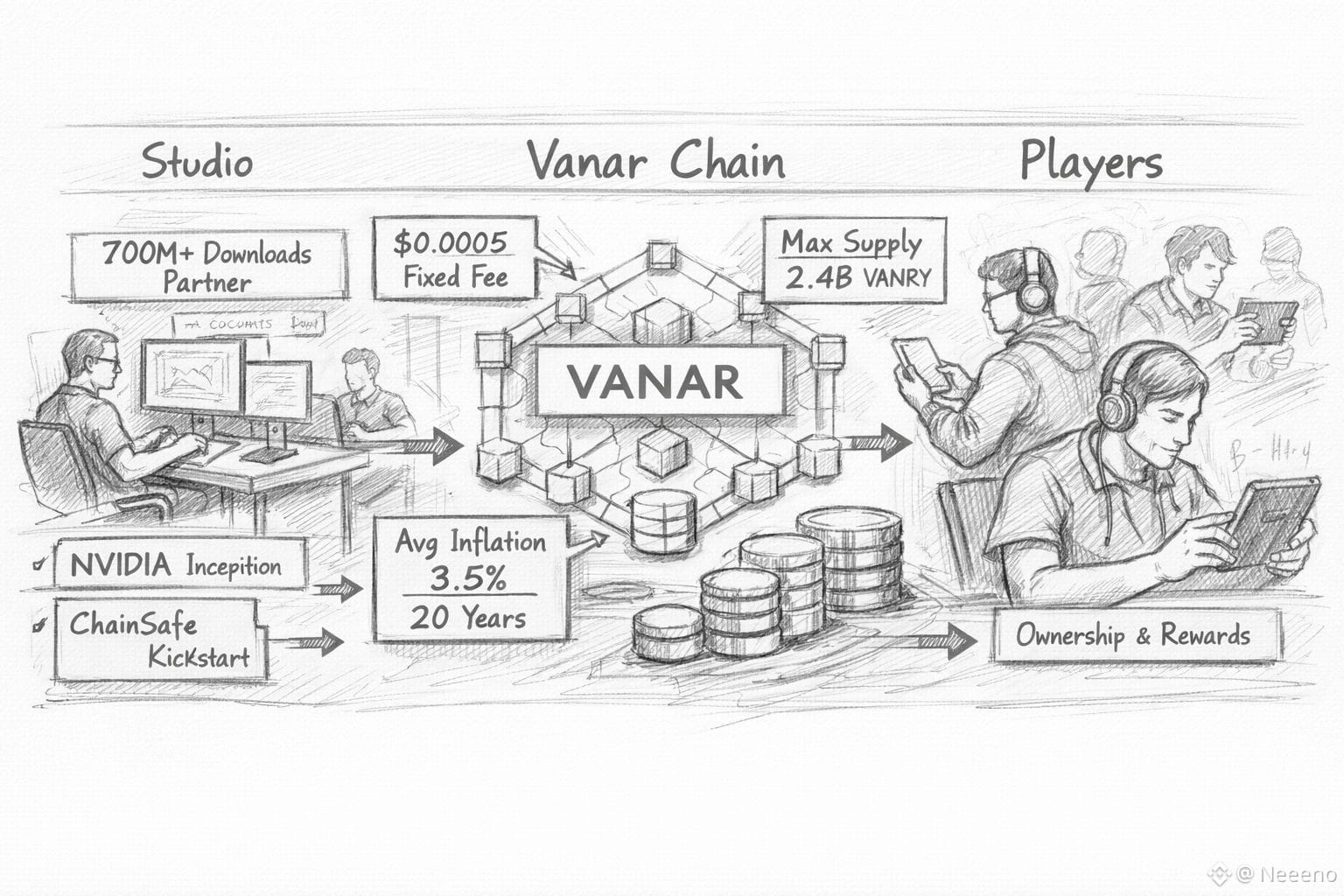

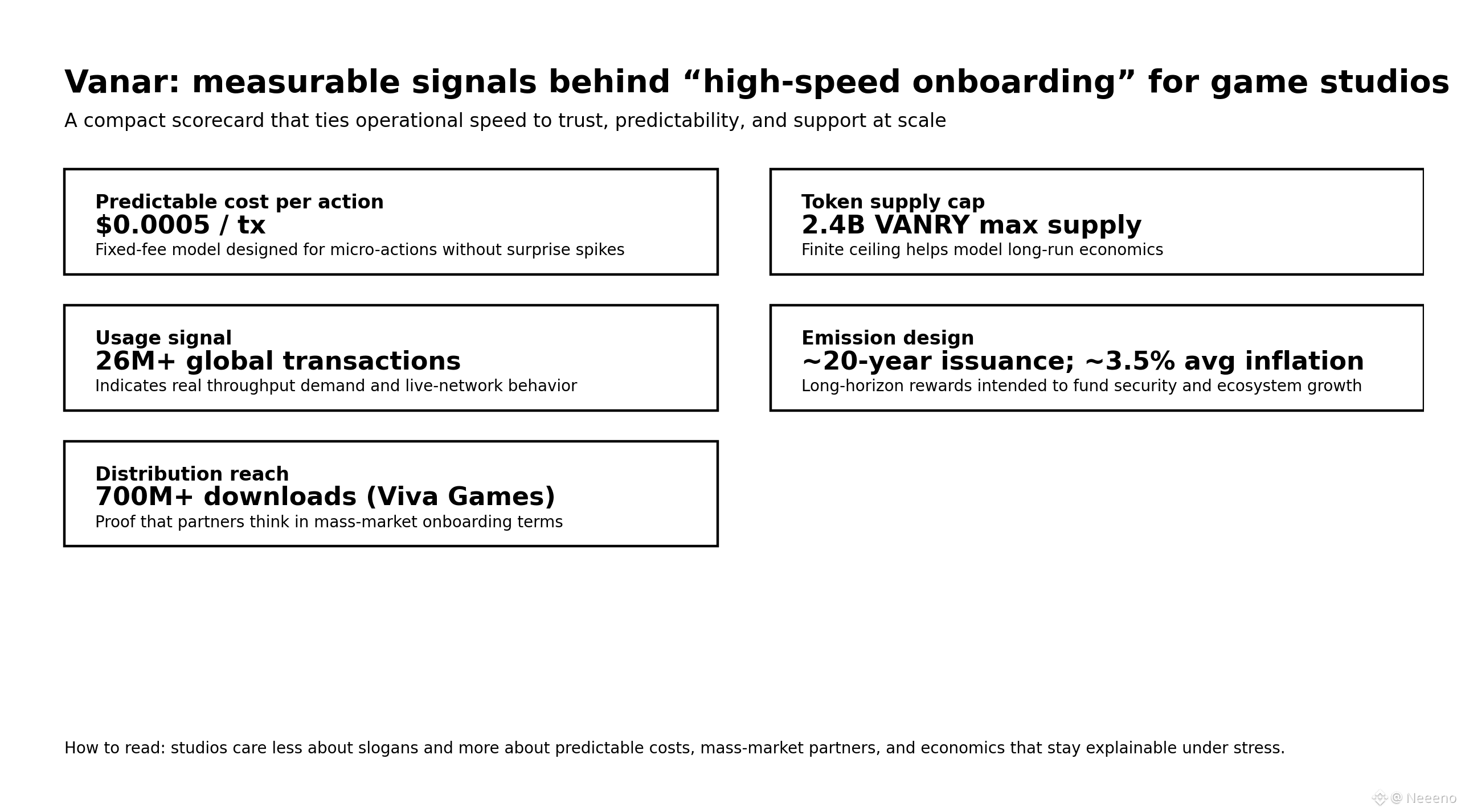

This is where the Viva Games Studios relationship becomes more than a logo on a partner page. Viva is described as operating across more than 10 studios with 700M+ downloads, and with a track record tied to big entertainment brands. That scale changes the conversation because it forces Vanar to care about onboarding as a mass-market discipline, not a niche feature. When your partner’s world is measured in hundreds of millions of installs, you can’t hide behind “early adopter” excuses. Whatever you build has to survive messy devices, inconsistent networks, impatient users, and the reality that customer support will be blamed for anything that feels confusing.

There’s also a psychological reason studios like the presence of a large, established game operator in the room: it reduces social risk inside the studio. The hardest part of adopting new infrastructure is rarely technical. It’s internal credibility. A lead engineer or product owner has to defend the decision when something goes wrong, and in games something always goes wrong. Partnerships that signal “this path has been walked by people who ship at scale” make those internal conversations easier. It’s not that studios outsource thinking. It’s that they want fewer unknowns when they’re already taking creative risk.

Then there’s the less glamorous layer: money movement and cost predictability. Studios don’t just fear downtime—they fear unpredictable unit economics. A game can survive a lot of things, but it struggles when costs become volatile right as usage spikes. Vanar’s public developer messaging leans into fixed, predictable pricing, even stating a dollar-denominated transaction cost of $0.0005. The number matters less than the promise behind it: teams can model costs without praying the network behaves. In practice, predictable fees are also a fairness tool. When costs are stable, whales can’t crowd out normal players simply by being willing to pay more during congestion. That kind of fairness shows up in player sentiment long before anyone can articulate it.

Speed, in this context, is not just “fast blocks.” It’s operational speed: the ability to run a live game without treating every on-chain interaction like a special event. Onboarding is faster when you can assume actions will settle consistently, support tickets will be explainable, and the system won’t surprise you at scale. This is also why Vanar keeps investing in an ecosystem approach around teams, tooling, and external partners—because a studio doesn’t ship with a chain alone. It ships with auditors, security reviewers, wallet experiences, account flows, and integration specialists who know how to keep the game feeling like a game.

Vanar’s Kickstart-related partner announcements are revealing here, even when they read like operational updates. When a network brings in a development partner like ChainSafe—described as offering consultations, discounted co-development, and priority onboarding support—it’s addressing a real studio pain: the shortage of people who can do this work without slowing everything down.Studios want to move fast, but not by taking risky shortcuts. They want people who’ve seen integrations break before, know the common traps, and can keep releases moving.

Speed matters, but “safe speed” matters more. Studios prefer partners who understand where things usually fail and can help the team keep shipping without chaos.

Studios don’t just want fast work—they want dependable fast work. They look for someone who knows the danger spots from experience and can keep the build process steady.

Another reason studios lean toward Vanar for onboarding is that it doesn’t pretend games are tidy. Games often have conflicting “truths.” The server says one thing, the player’s device says another, and players will take advantage of any gray area.

When ownership and economies enter the picture, those disagreements become higher-stakes. Players will argue that they “earned” something even if the system says otherwise. Fraud teams will argue a transaction was malicious while a legitimate player insists it was a bug.The systems that last aren’t the ones that claim nothing will ever go wrong. They’re the ones that can settle arguments clearly. That’s why clear proof and easy checking matters—it stops people from feeling like they lost something for no reason, which can turn a community angry fast.

This is also where the token becomes part of the trust story, not just a market story. VANRY is described as the native token used for transaction fees, staking, validator support, and governance, and it’s explicitly framed as the unit that aligns network security with usage. The point for studios is not “token upside.” The point is whether the network’s incentives reward stability over chaos. When validators and operators are rewarded over long horizons, and when issuance is structured rather than improvised, studios feel like they’re building on something that won’t change its personality mid-season.

The token data helps here because it turns vibes into something checkable. Publicly available disclosures describe a total supply of 2.4 billion VANRY, with an initial split that includes a large genesis allocation tied to a 1:1 swap and additional allocations for validator rewards, development rewards, and community incentives. Separately, Vanar’s documentation describes a long issuance horizon—additional tokens minted as block rewards over about 20 years—and references an average inflation rate of around 3.5% over that period. For a studio, this kind of structure matters because it signals whether the system is designed to be operated, not just launched. It’s hard to build player trust on top of an economy that feels like it might be rewritten every quarter.

Recent ecosystem updates also show how Vanar has kept expanding the “onboarding surface area” beyond pure gaming. Joining programs like NVIDIA Inception, and public discussions of partnerships with infrastructure providers like Google Cloud, aren’t gaming announcements on paper, but they’re gaming-relevant in practice because game onboarding is ultimately a reliability problem: latency, scalability, global distribution, and the ability to support teams building complex products without constant reinvention. The studio experience improves when the chain’s broader partnerships reduce operational unknowns. Even if a player never hears those names, they feel the difference when things don’t lag, don’t fail mysteriously, and don’t require arcane steps.

When you zoom out, you can see why “high-speed onboarding” is becoming the lens through which major studios evaluate Vanar. It’s not a single capability. It’s the compound effect of predictable costs, partner support that reduces integration risk, and an economic structure that tries to keep the system stable across years—not weeks.The studios that act first are usually the ones who already know this: it’s easy to lose player trust, and hard to earn it back. If the first steps feel like a trick, players leave. If ownership feels unfair, players revolt. If support can’t explain what happened, players assume the worst.

And there’s a final, quieter layer: responsibility. A game studio onboarding millions onto any new system is taking responsibility for failure modes most people never think about. Lost credentials. Disputed purchases. Exploits that spread on social media in hours. Pressure from partners and licensors who don’t care about crypto nuance, only brand safety. Under those conditions, the infrastructure that wins is the one that behaves like invisible plumbing. Vanar’s public materials keep circling back to that idea of making the experience feel normal while the complexity stays behind the curtain, and backing that with concrete levers: fixed pricing that can be modeled, a token supply and issuance structure that is disclosed, and an ecosystem strategy that brings in operators and builders who’ve lived through production chaos.

In the end, the reason major gaming studios are choosing Vanar for high-speed onboarding is not that they want attention. It’s that they want the opposite. They want onboarding that doesn’t become the story. They want reliability that doesn’t demand heroics. They want an economy where the unit of work—whether paid in time, trust, or VANRY—doesn’t behave unpredictably when the game finally succeeds. A chain can be loud and still fail a studio. The systems that survive are the ones that stay reliable. They don’t wobble when people are impatient, markets get loud, or bugs appear—they still do what they promised.