When I look at Vanar, I don’t approach it as a token or even as a piece of novel technology. I think of it as an attempt to solve a very ordinary problem: how to make digital systems usable at scale without asking people to understand how they work. That framing shapes everything for me. Instead of focusing on abstractions, I pay attention to what the system seems to assume about real users, their patience, their habits, and the limits of their attention.

What becomes clear is that Vanar is designed around the idea that most users will arrive through familiar environments like games, entertainment platforms, or branded experiences. These users are not experimenting. They are not exploring. They are there to do something specific, and they expect it to work the same way every time. That expectation is unforgiving. Any friction, delay, or confusion breaks trust immediately. Vanar’s design choices suggest an awareness of this reality, and an acceptance that infrastructure should adapt to people, not the other way around.

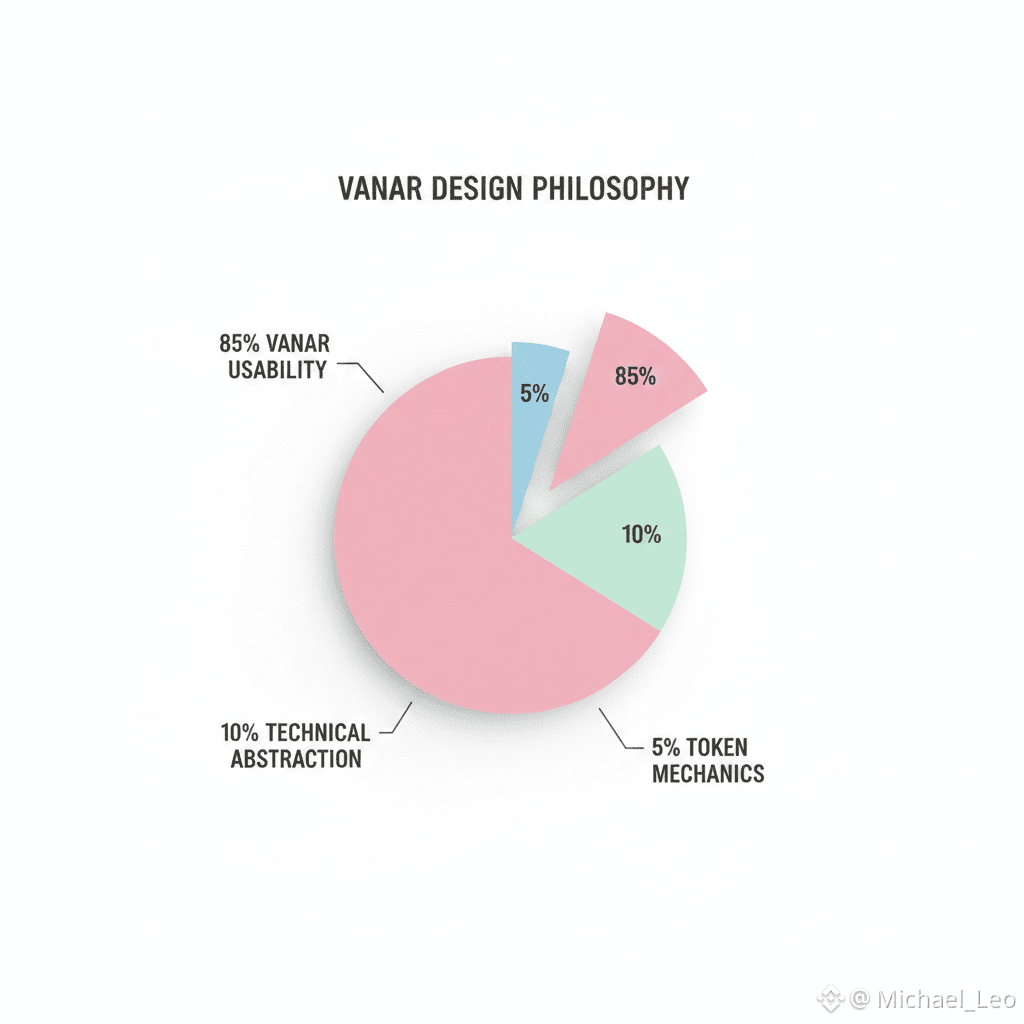

I find the team’s background reflected less in technical claims and more in what is deliberately avoided. There is very little emphasis on exposing internal mechanics to the end user. Instead, the system seems structured to absorb complexity internally, so that the surface experience remains stable. This is a quiet but meaningful decision. In practice, scalable systems succeed when they reduce the number of decisions a user has to make, not when they increase transparency for its own sake.

Looking at how Vanar supports multiple verticals, I don’t see a desire to be everywhere. I see a need to be resilient under different types of stress. Games test responsiveness and state persistence. Entertainment platforms test onboarding and identity continuity. Brand and eco-focused applications test reliability and cost predictability. These environments are not forgiving, and they don’t tolerate excuses. If something fails, users don’t wait for explanations; they leave. Designing infrastructure that can survive these conditions is less about ambition and more about discipline.

Looking at how Vanar supports multiple verticals, I don’t see a desire to be everywhere. I see a need to be resilient under different types of stress. Games test responsiveness and state persistence. Entertainment platforms test onboarding and identity continuity. Brand and eco-focused applications test reliability and cost predictability. These environments are not forgiving, and they don’t tolerate excuses. If something fails, users don’t wait for explanations; they leave. Designing infrastructure that can survive these conditions is less about ambition and more about discipline.

Projects like Virtua Metaverse and the VGN games network feel important precisely because they are not theoretical. They introduce ongoing activity, unpredictable behavior, and real user expectations into the system. These are the conditions under which infrastructure either proves itself or quietly breaks. I tend to trust systems more when they are shaped by these pressures rather than by idealized use cases.

The role of the VANRY token, viewed through this lens, feels utilitarian. It exists to support usage, coordination, and continuity within the system rather than to demand attention. When a token functions properly, users don’t have to think about it explicitly. It becomes part of the background logic that keeps things moving. That kind of invisibility is often a sign of alignment, not weakness.

What Vanar ultimately represents to me is a particular philosophy of building. One that accepts that most people do not want to learn new systems, manage complexity, or adjust their behavior to fit infrastructure. They want infrastructure to disappear. If Vanar continues to lean into this mindset, it points toward a future where blockchain-based systems earn relevance by being dependable, unremarkable, and quietly present. In my experience, those are the systems that last.