I used to think the hardest part of building autonomous systems was making them smart enough. Better models, better decision logic, more context. After watching real systems move from prototypes into continuous operation, that belief didn’t survive long. Intelligence rarely breaks systems. People do.

Not people as users, but people as an implicit dependency inside the infrastructure.

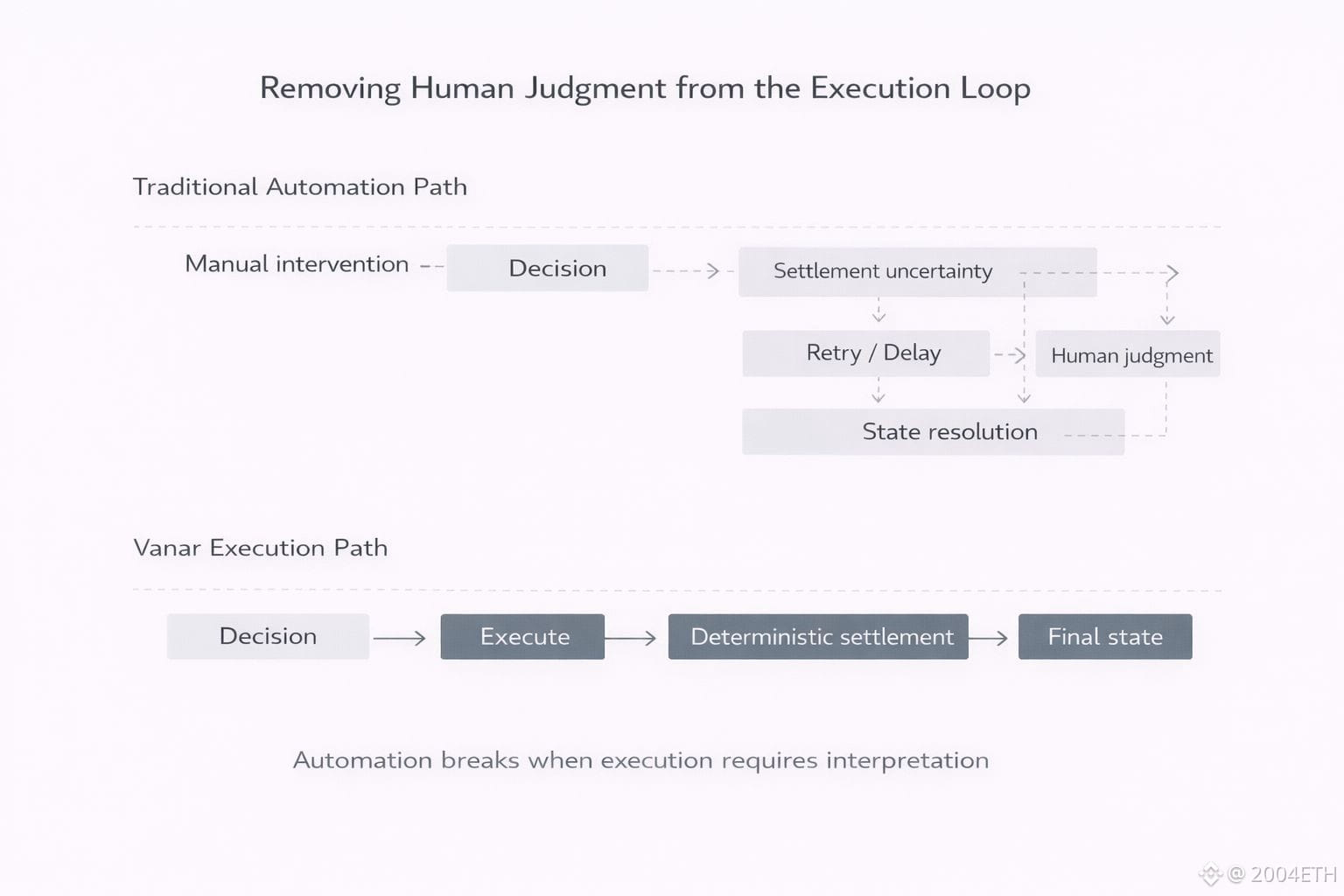

Most automated systems don’t fail loudly. They slowly accumulate moments where a human needs to step in. A fee spikes unexpectedly. Finality takes longer than expected. A transaction lands in an ambiguous state. None of these are catastrophic on their own. In fact, they look harmless when humans are in the loop. Someone notices. Someone waits. Someone decides what to do next.

The problem is that every one of those moments reintroduces human judgment into a system that was supposed to run without it.

That judgment becomes a form of technical debt.

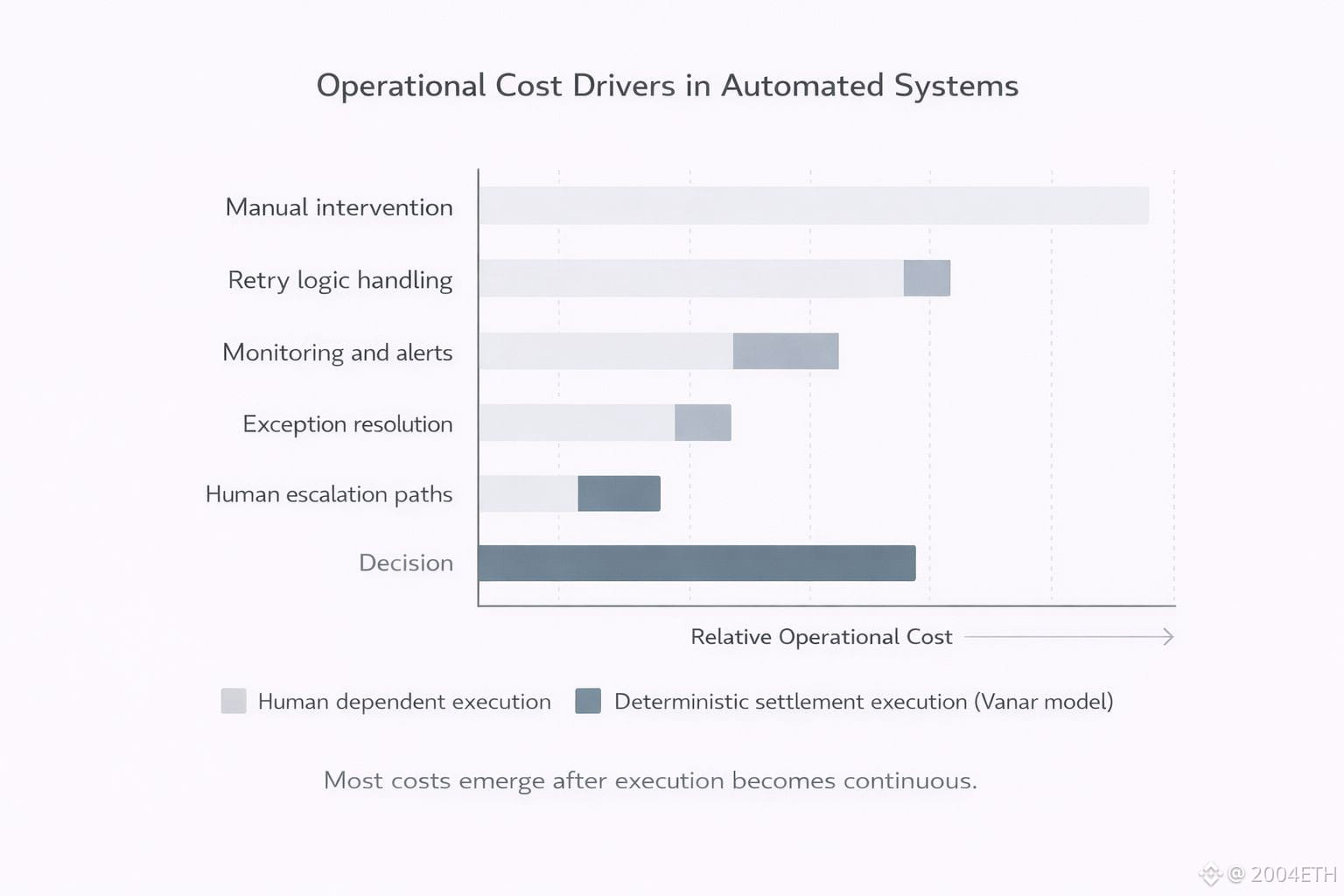

At small scale, it’s invisible. At large scale, it becomes the dominant cost.

This is where my view of automation changed. A system is not autonomous because it can make decisions. It is autonomous because it does not require interpretation when something deviates from the happy path. The moment an operator has to decide whether to retry, delay, override, or escalate, the system is no longer running itself. It is being managed.

Most blockchain infrastructure today quietly assumes that management layer will always exist. That assumption is reasonable if the primary actor is a human. Humans are good at absorbing uncertainty. We can tolerate variability in fees. We can come back later if finality is delayed. We can interpret unclear outcomes.

Automated systems cannot.

When execution is continuous, uncertainty does not pause the system. It branches it. Retry logic multiplies. Monitoring becomes mandatory. Alerting escalates. What was meant to be a simple loop turns into a web of exceptions, each one requiring oversight. Over time, the system becomes harder to operate than the process it was meant to automate.

This is the hidden cost of human judgment in automated environments.

Vanar makes sense to me because it starts from this failure mode, not from a feature list.

Its design assumes that machines will act continuously and without supervision. That assumption immediately constrains what the infrastructure can afford to be ambiguous about. Settlement cannot be something that usually works. It cannot depend on best effort outcomes or social resolution. It has to be predictable enough to sit inside the execution path itself.

This is not a neutral design choice.

Predictability comes with trade offs. It reduces flexibility. It limits how much behavior can be adjusted on the fly. It narrows optionality during abnormal conditions. Many systems avoid this because flexibility feels powerful early on. You can respond to more situations. You can patch around problems. You can adapt.

But that flexibility is exactly what creates long term operational fragility.

Every adjustable parameter is another place where judgment leaks back in. Every exception path is another decision that someone, or something, must interpret. Vanar deliberately accepts tighter constraints to remove that layer of interpretation. Instead of asking automated systems to adapt to changing execution conditions, it enforces conditions that those systems can assume.

From an operator’s perspective, this changes everything.

Logic becomes simpler because fewer branches exist. Monitoring becomes lighter because fewer things can go wrong in undefined ways. Failure handling becomes deterministic rather than procedural. When something breaks, the system does not ask what should happen. It already knows.

This also reframes how value movement is treated.

In many systems, settlement is an external dependency. Execution happens first. Settlement follows, sometimes immediately, sometimes later, sometimes after reconciliation. That separation is manageable when humans are present to close the gaps. It is dangerous when systems are expected to coordinate without communication.

Vanar treats settlement as part of execution itself. An action is not complete until value movement is final and observable by the rest of the system. That shared assumption is what allows independent automated actors to coordinate without checking in with each other or with an operator. State is not inferred. It is known.

This is where the cost of autonomy actually lives.

It does not show up primarily in transaction fees. It shows up in retries, dashboards, alert fatigue, escalation paths, and human oversight. Each layer exists to compensate for uncertainty. When settlement becomes predictable enough to be assumed, entire categories of overhead disappear.

VANRY’s role is easier to understand through this lens.

It is not designed to incentivize clicks or maximize visible activity. It underpins participation in a system where value movement is expected to occur as part of automated processes. The token sits inside execution, not at the edge of user interaction. That only works if settlement can be relied on without negotiation.

What I find compelling about Vanar is not that it promises fewer failures. No real system can do that. It assumes failures will happen. The difference is that failure resolution is designed to be deterministic, not interpretive. There is no moment where someone needs to decide what the system should do next.

That assumption reshapes the architecture.

Over time, fewer assumptions mean less complexity. Less complexity reduces operational cost. The system becomes quieter, not because nothing is happening, but because fewer things demand attention. This is the kind of quiet that matters when systems are expected to keep running day after day.

There is a tendency to think autonomy exists on a spectrum. In production environments, it doesn’t. Either a system can run without intervention, or it eventually drifts back toward manual control, regardless of how advanced it looks on paper.

Vanar feels built with that binary reality in mind.

It does not optimize for attention or flexibility in the short term. It optimizes for endurance. For systems that cannot pause. For processes that cannot wait for someone to notice something went wrong.

Human judgment is valuable, but it does not scale inside automated loops. Every place it appears is a liability. Vanar’s design is essentially a decision to pay the cost of constraint upfront in order to remove the cost of judgment later.

For long running automated systems, flexibility is attractive early on. Predictability is what keeps them alive over time.

That is the trade off Vanar makes, and it is one that only becomes obvious once you’ve seen systems fail quietly, not because they weren’t intelligent enough, but because they depended on someone being there when things stopped behaving.