When I first looked at "Walrus", I assumed it would follow the familiar playbook. Big throughput numbers. Aggressive benchmarks. A clear pitch about being “faster,” “cheaper,” or “bigger” than existing decentralized storage systems. That expectation didn’t survive long.

When I first looked at "Walrus", I assumed it would follow the familiar playbook. Big throughput numbers. Aggressive benchmarks. A clear pitch about being “faster,” “cheaper,” or “bigger” than existing decentralized storage systems. That expectation didn’t survive long.

The more time I spent reading Walrus, the clearer it became that it isn’t trying to be impressive in the usual ways. In fact, it seems almost indifferent to being noticed at all. And that indifference explains a lot about the kind of system it’s becoming.

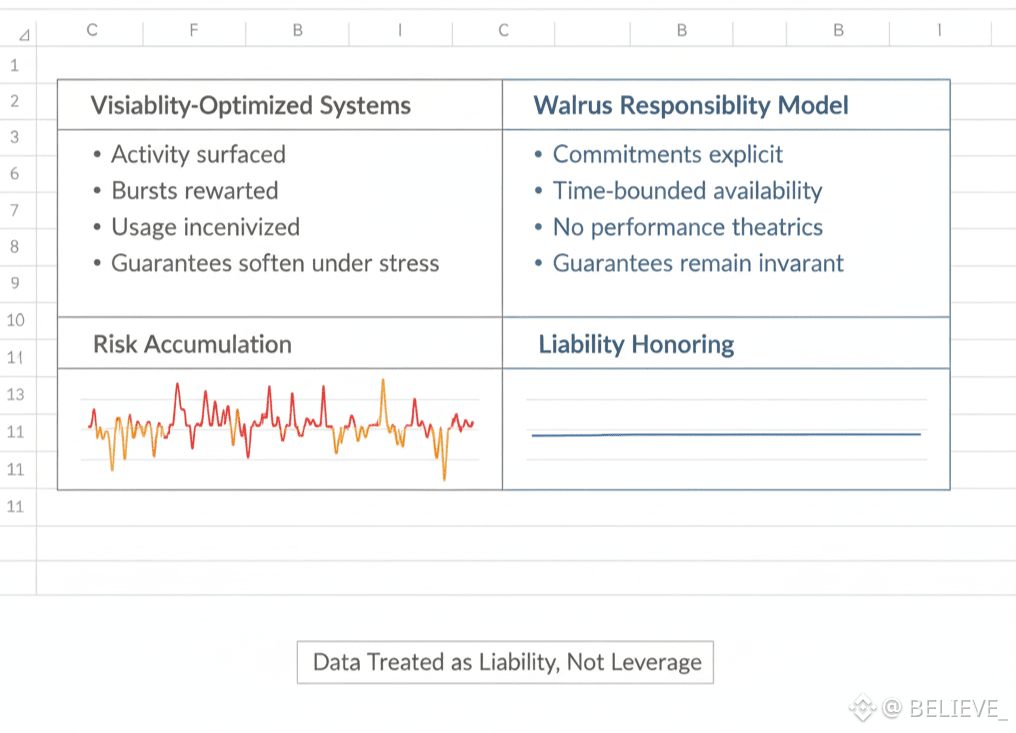

Most infrastructure projects compete for visibility because visibility brings adoption. Metrics get highlighted. Dashboards get polished. Activity becomes something to showcase. Walrus takes a quieter route. It doesn’t ask how to make data noticeable. It asks how to make data boring in the best possible sense.

That sounds counterintuitive until you think about what storage is actually for.

Data that matters isn’t data you want to watch. It’s data you want to forget about — until the moment you need it. The ideal storage system fades into the background. It doesn’t ask for attention. It doesn’t surprise you. It just holds.

Walrus seems designed around that assumption.

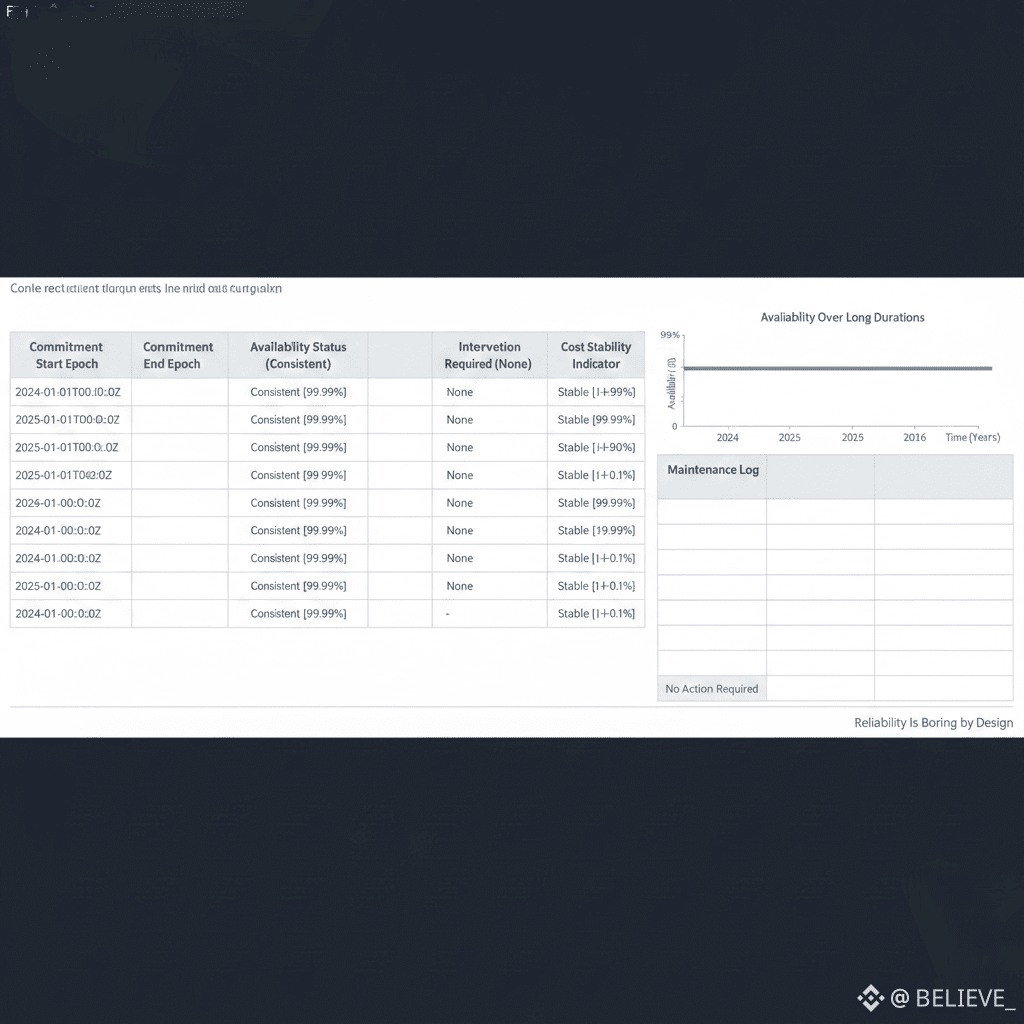

Instead of optimizing for peak moments, it optimizes for long stretches of uneventful time. Data sits. Time passes. Nothing breaks. Nothing needs intervention. That’s not exciting. But it’s rare.

A lot of decentralized systems struggle here because they inherit incentives from more expressive layers. Activity is rewarded. Interaction is surfaced. Usage becomes something to stimulate. Storage, under those incentives, starts behaving like a stage rather than a foundation.

Walrus resists that drift. It treats storage as a commitment, not a performance. Once data is written, the system’s job isn’t to extract value from it. The job is to stay out of the way.

That design choice shows up everywhere.

Storage on Walrus isn’t framed as “forever by default.” It’s framed as intentional. Data stays available because someone explicitly decided it should. When that decision expires, responsibility ends. There’s no pretense of infinite persistence and no silent decay disguised as permanence.

What’s interesting is how this affects behavior upstream.

When storage isn’t automatically eternal, people think differently about what they store. Temporary artifacts stay temporary. Important data gets renewed. Noise stops accumulating just because it can. Over time, the system doesn’t fill up with forgotten remnants of past experiments.

That selectivity is subtle, but it compounds.

Another thing that stood out to me is how little Walrus tries to explain itself to end users. There’s no attempt to turn storage into a narrative. No effort to brand data as an experience. That restraint matters. Systems that explain themselves constantly tend to entangle themselves with expectations they can’t sustain.

Walrus avoids that trap by focusing on invariants instead of stories.

Data exists.

It remains available for a known window.

Anyone can verify that fact.

Nothing more needs to be promised.

This becomes especially important under stress. Many systems look solid until demand spikes or conditions change. When usage surges unexpectedly, tradeoffs appear. Performance degrades. Guarantees soften. Users are suddenly asked to “understand.”

Walrus is structured to minimize those moments. Because it isn’t optimized around bursts of attention, it isn’t fragile when attention arrives. Data doesn’t suddenly become more expensive to hold. Availability doesn’t become conditional on network mood. The system doesn’t need to renegotiate its role.

That predictability is hard to appreciate until you’ve relied on systems that lack it.

There’s also a philosophical difference at play. Many storage networks treat data as an asset to be leveraged. Walrus treats data as a liability to be honored. That flips incentives. The goal isn’t to maximize how much data enters the system. It’s to ensure that whatever does enter is treated correctly for as long as promised.

This is not the kind of framing that excites speculation. It doesn’t create dramatic narratives. It does, however, create trust through repetition.

Day after day, data behaves the same way.

That’s how habits form.

One risk with this approach is obvious. Quiet systems are easy to overlook. If adoption doesn’t materialize organically, there’s no hype engine to compensate. Walrus seems comfortable with that risk. It isn’t trying to be everything to everyone. It’s narrowing its responsibility deliberately.

That narrowing has consequences. Fewer surface-level integrations. Slower visible growth. Less noise. But it also avoids a different risk: being pulled in too many directions at once.

As infrastructure matures, the systems that last are rarely the ones that tried to capture every use case early. They’re the ones that chose a narrow responsibility and executed it consistently until it became invisible.

Walrus feels aligned with that lineage.

What makes this particularly relevant now is how the broader ecosystem is changing. As more value moves on-chain, the tolerance for unreliable foundations drops. People stop asking what’s possible and start asking what’s dependable. Storage stops being an experiment and starts being an expectation.

In that environment, systems that behave predictably under boredom matter more than systems that perform under excitement.

Walrus doesn’t try to convince you it’s important. It assumes that if it does its job well enough, you won’t think about it at all.

That’s a risky bet in a space driven by attention.

It’s also how real infrastructure tends to win.

If Web3 continues to mature, the systems that disappear into routine will end up carrying the most weight. Not because they were loud, but because they were there — every time — without asking to be noticed.

Walrus feels like it’s building for that future.