The Bandwidth Problem Nobody Discusses

Most decentralized storage systems inherit a hidden cost from traditional fault-tolerance theory. When a node fails and data must be reconstructed, the entire network pays the price—not just once, but repeatedly across failed attempts and redundant transmissions. A blob of size B stored across n nodes with full replication means recovery bandwidth scales as O(n × |blob|). You're copying the entire dataset from node to node to node. This is tolerable for small files. It becomes ruinous at scale.

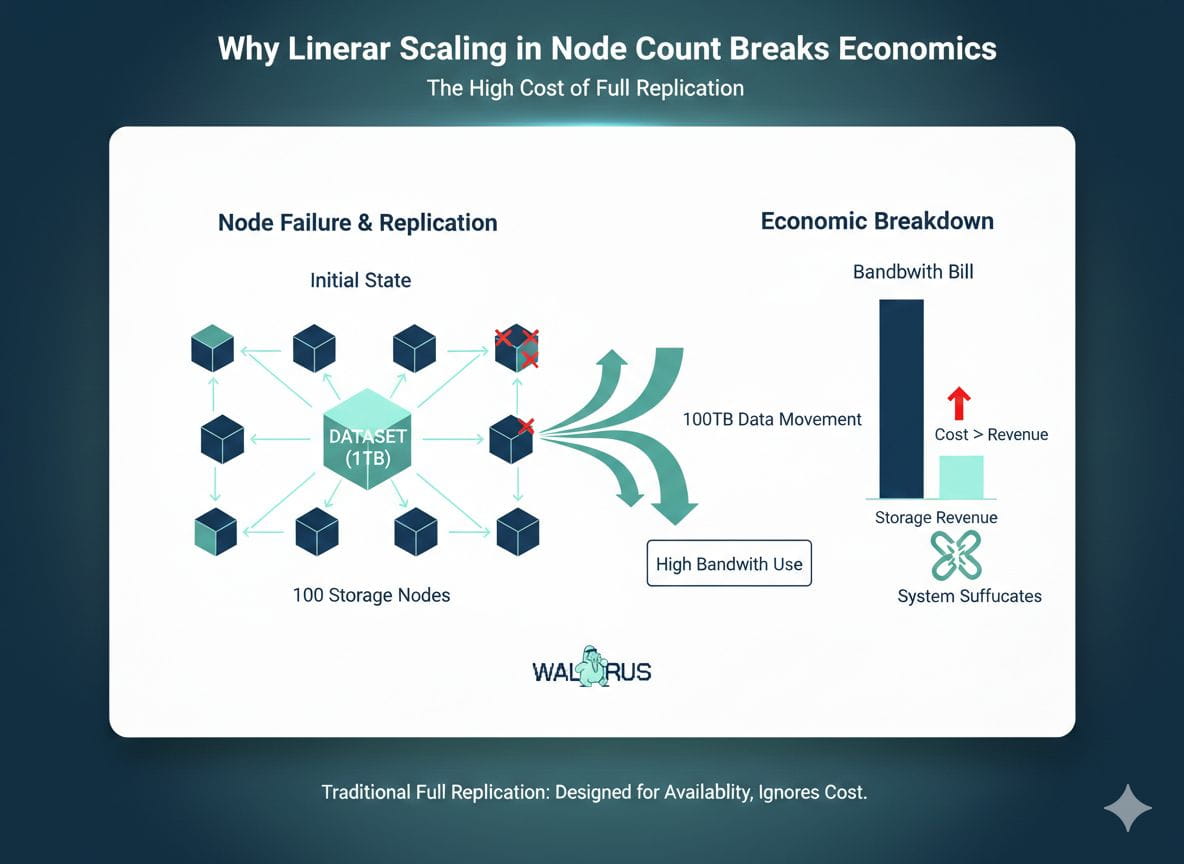

Why Linear Scaling in Node Count Breaks Economics

Consider a 1TB dataset spread across 100 storage nodes. Full replication means that when any node drops, you're potentially moving 100TB across the network to restore balance. Add failures over months, and your bandwidth bill exceeds your revenue from storage fees. The system suffocates under its own overhead. This is not a theoretical concern—it's why earlier decentralized storage attempts never achieved meaningful scale. They optimized for availability guarantees but ignored the cost of maintaining them.

Erasure Coding's Promise and Hidden Trap

Erasure coding helped by reducing storage overhead. Instead of copying the entire blob n times, you fragment it into k parts where any threshold of them reconstructs the original. A 4.5x replication factor beats 100x. But here's what many implementations miss: recovery bandwidth still scales with the total blob size. When you lose fragments, you must transmit enough data to reconstruct. For a 1TB blob with erasure coding, recovery still pulls approximately 1TB across the wire. With multiple failures in a month-long epoch, you hit terabytes of bandwidth traffic. The math improved, but the pain point persisted.

Secondary Fragments as Bandwidth Savers

Walrus breaks this pattern through an architectural choice most miss: maintaining secondary fragment distributions. Rather than storing only the minimal set of erasure-coded shards needed for reconstruction, nodes additionally hold encoded redundancy—what the protocol terms "secondary slivers." These are themselves erasure-coded derivatives of the primary fragments. When a node fails, the system doesn't reconstruct from scratch. Instead, peers transmit their secondary slivers, which combine to recover the lost fragments directly. This sounds subtle. It's transformative.

The Proof: Linear in Blob Size, Not Node Count

The recovery operation now scales as O(|blob|) total—linear only in the data size itself, independent of how many nodes store it. Whether your blob lives on 50 nodes or 500, recovery bandwidth remains constant at roughly one blob's worth of transmission. This is achieved because secondary fragments are already distributed; no node needs to pull the entire dataset to assist in recovery. Instead, each peer contributes a small, pre-computed piece. The pieces combine algebraically to restore what was lost.

Economics Shift From Prohibitive to Sustainable

This distinction matters in ways that reach beyond engineering. A storage network charging $0.01 per GB per month needs recovery costs below revenue. With O(n|blob|) bandwidth, a single month of failures on large blobs erases profit margins. With O(|blob|) recovery, bandwidth costs become predictable—roughly equivalent to storing the data once per month. Operators can price accordingly. Markets can function. The system scales.

Byzantine Resilience Without Coordination Tax

Secondary fragments introduce another benefit rarely articulated: they allow recovery without requiring consensus on which node failed or when recovery should trigger. In synchronous networks, you can halt and coordinate. In the asynchronous internet that actually exists, achieving agreement on failure is expensive. Walrus nodes can initiate recovery unilaterally by requesting secondary slivers from peers. If adversaries withhold them, the protocol detects deviation and escalates to on-chain adjudication. This decouples data availability from the need for tight Byzantine agreement at recovery time.

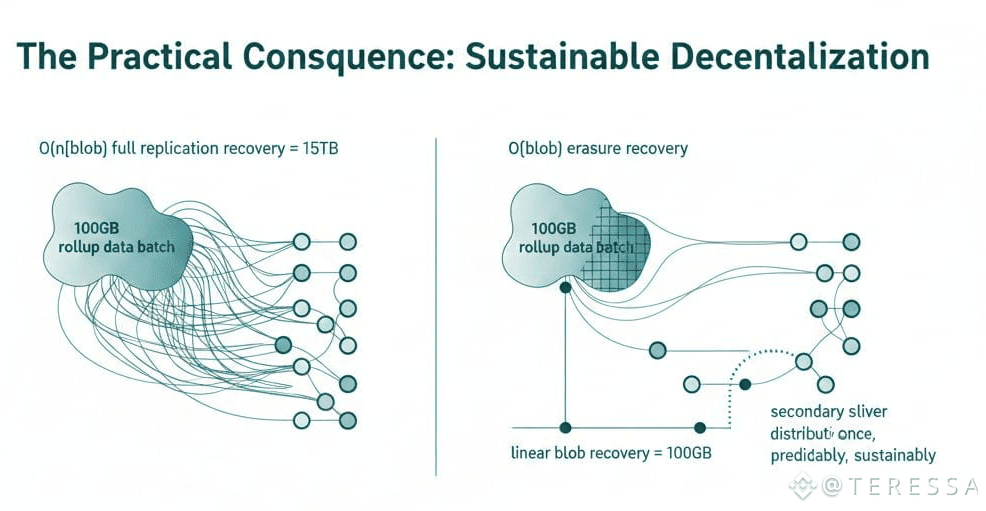

The Practical Consequence: Sustainable Decentralization

The gap between O(n|blob|) and O(|blob|) recovery appears abstract until you model real scenarios. A 100GB rollup data batch replicated across 150 nodes: full replication recovery costs 15TB. Erasure with linear blob recovery still costs 100GB. But erasure with secondary sliver distribution costs 100GB once, predictably, sustainably. Scale this to petabytes of data across thousands of nodes, and the difference separates systems that work from systems that hemorrhage resources.

Why This Matters Beyond Storage

This recovery model reflects a deeper principle: Walrus was built not from theory downward but from operational constraints upward. Engineers asked what would break a decentralized storage network at scale. Bandwidth during failures topped the list. They designed against that specific pain point rather than accepting it as inevitable. The result is a system where durability and economics align instead of conflict—where maintaining data availability doesn't require choosing between credible guarantees and affordability.