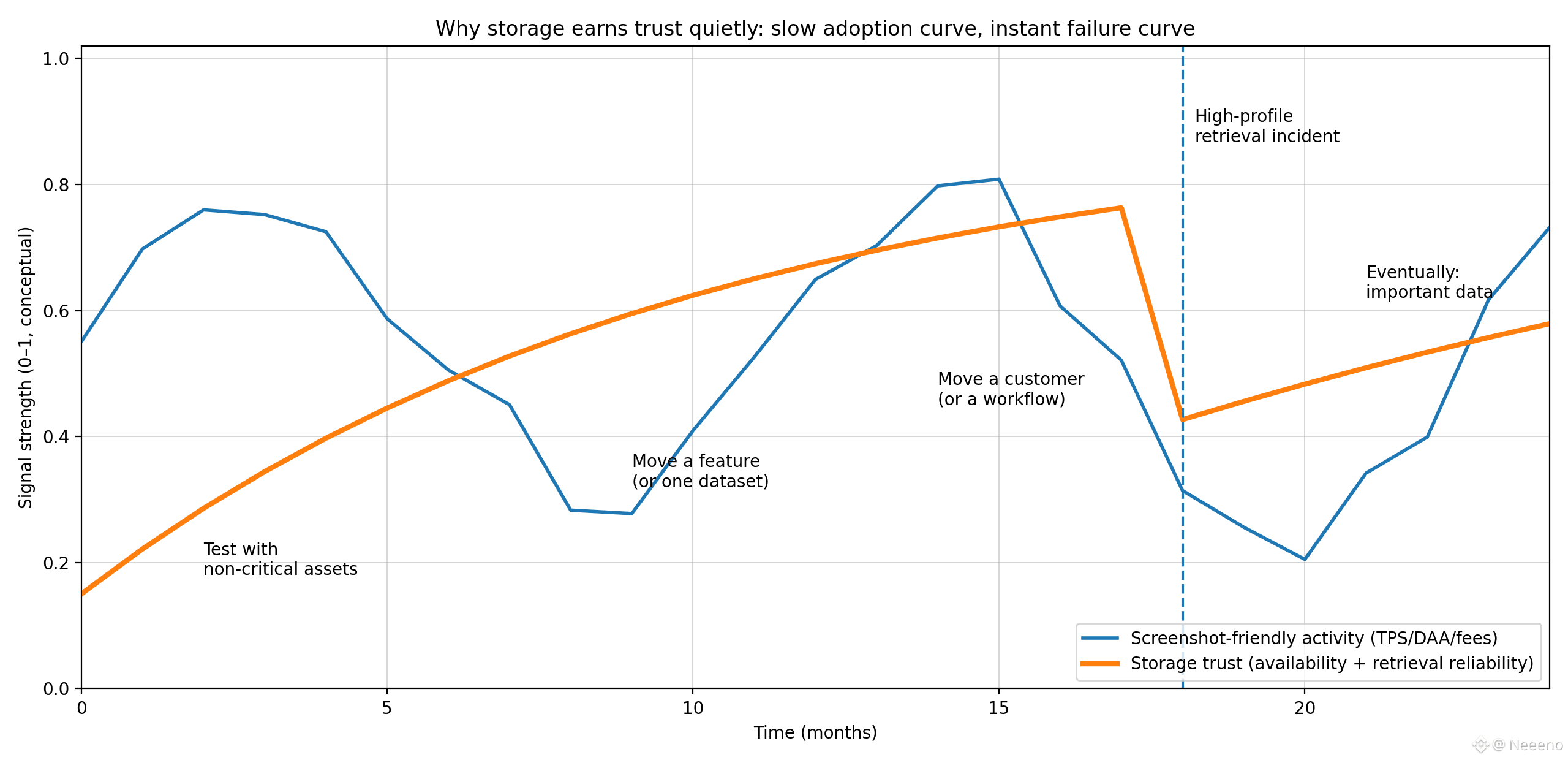

@Walrus 🦭/acc Crypto loves the numbers you can screenshot. Transactions per second, daily active addresses, fee charts, leaderboard games. Those metrics can be useful, but they also reward what is loud and immediate. Storage earns trust in a quieter way. If you are building something that has to load every day for real users, the questions change fast: will the data still be there next week remembering that half your nodes will churn, a region will go dark, and someone will try to cut corners? Will retrieval stay fast enough that the product feels normal, not like a science project? Will costs be boring and predictable instead of swinging with attention? In storage, the “metric” that matters is whether teams stop thinking about it because it keeps working.

Walrus, in plain terms, is a decentralized protocol for storing large blobs of data and retrieving them reliably, with an eye toward applications that are content-heavy or data-heavy. The point is not to squeeze files into a chain. The point is to give developers a storage layer that behaves more like infrastructure than a novelty: you put large objects in, you can fetch them back, and you can do that repeatedly without negotiating with a single hosting provider. Walrus positions this as blob storage meant to support high-throughput usage where availability and recoverability are the real product.

That framing matters because storage is a harder promise than compute. Compute can look busy even when it is not doing anything important. You can generate activity, incentivize spam, or optimize for synthetic benchmarks. Storage is less forgiving. A network can’t bluff its way through years of “we’ll fetch that later” if later never arrives. The trust curve is slow: teams test with non-critical assets, then move one feature, then maybe one customer, then eventually something important. The failure curve is instant: one high-profile outage, one retrieval incident that corrupts confidence, and the migration narrative reverses overnight. That asymmetry is why storage protocols tend to feel conservative when they are serious.

Walrus tries to meet that conservatism with a security model that looks less like “who gets to produce the next block” and more like “who is economically accountable for keeping data available.

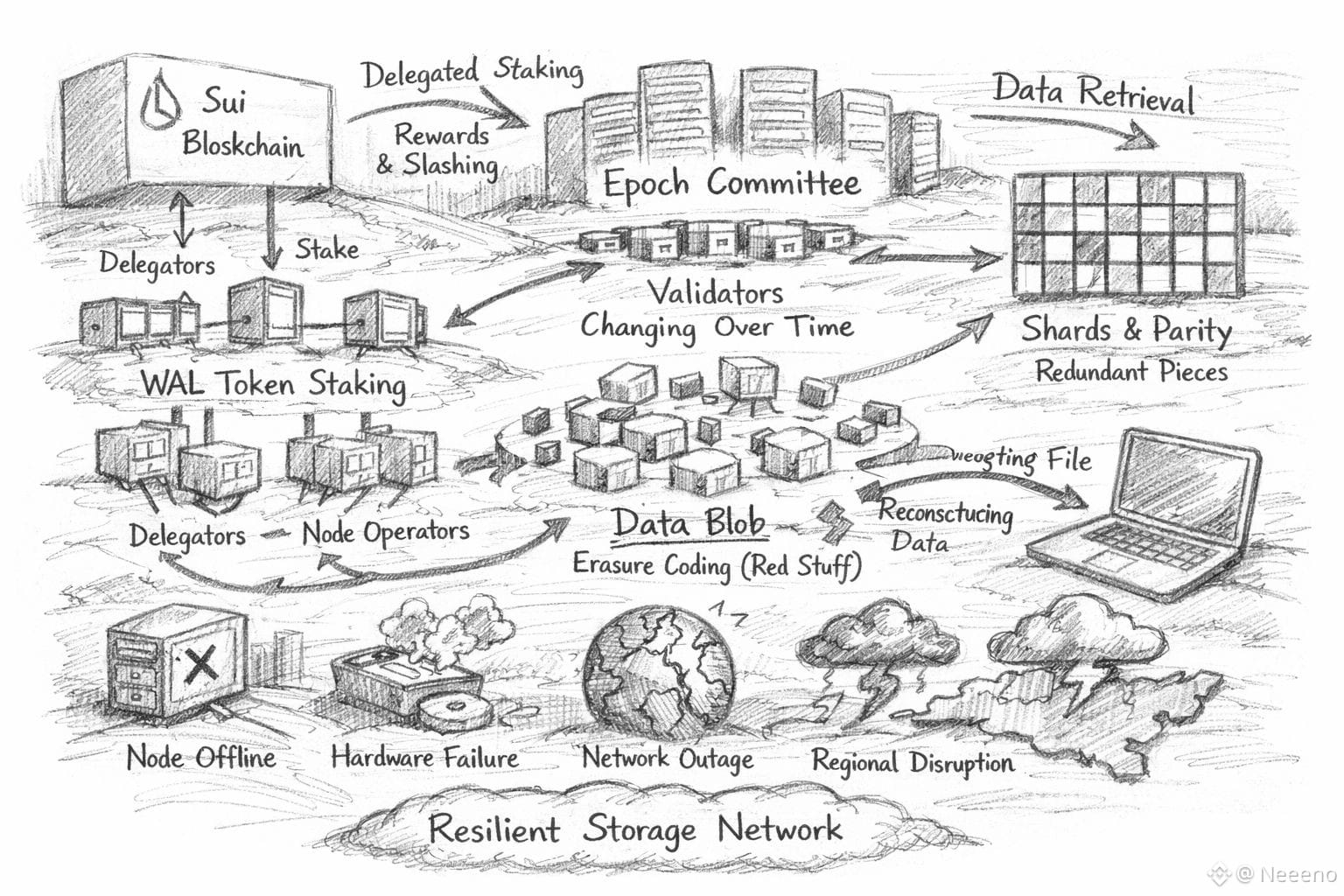

According to public docs, Walrus uses WAL as the staking token and lets holders delegate it to operators who run the storage infrastructure. Stake weight influences which operators are active and how incentives flow. The simple security bet is: if you put money at risk, it’s harder to fake reliability. If an operator wants to be trusted with serving data, they need stake behind them, and that stake can be penalized when they fail their obligations. Delegation also reflects social reality: most builders don’t want to become storage providers, but they can still participate in who gets trusted and how risk is priced.

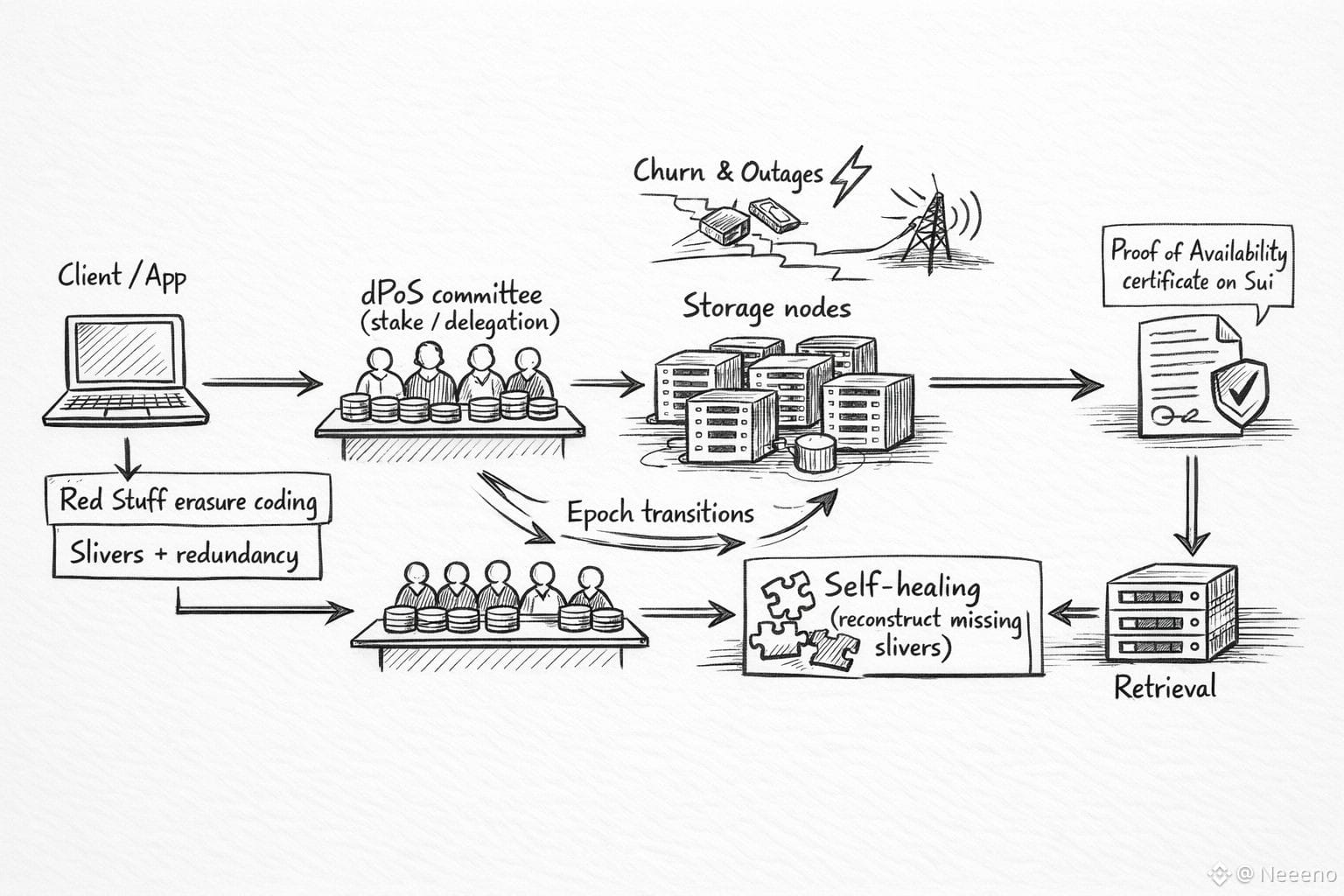

In Walrus, that stake-weighted selection ties into the idea of committees operating over epochs. An epoch is just a time window during which a chosen set of storage nodes is responsible for storing and serving data. If you squint, it’s a way to make the network legible: at any given moment, you can point to a specific set of accountable operators. At epoch boundaries, membership can change, and that is where real-world mess shows up. Nodes churn. Some operators disappear. Others come back. Hardware gets replaced. Networks reroute. Walrus’ design work treats churn as normal rather than exceptional, including mechanisms for changing committees without turning every transition into downtime.

The other core resilience idea is erasure coding, which is a fancy term for “don’t store the whole thing in one place, and don’t rely on full copies everywhere.” Walrus uses an erasure coding approach called Red Stuff.

Instead of keeping one full copy, the network breaks the file into many small parts and adds extra backup parts. If a few parts go missing, it can still rebuild the full file, so a few offline nodes won’t stop you from getting your data. You need enough pieces. This shifts the security story away from trusting any single operator and toward trusting the system’s ability to recover under partial failure.

That matters because storage failure modes are painfully ordinary. Operator churn is not a villain story; it’s economics and fatigue. Somebody’s server bill goes up, a hosting provider has an incident, a team rotates priorities, a region has connectivity problems, a power event knocks out equipment. Sometimes it’s mundane misconfiguration. Sometimes it’s a malicious operator seeing if they can collect rewards without doing the work. A storage network that assumes steady-state behavior is a storage network that will eventually disappoint you. The more honest approach is to assume everyday chaos as the baseline and build recovery paths that don’t require heroics or perfect coordination. The Walrus research describes mechanisms designed to keep availability through churn and to prevent adversaries from exploiting network delays to pass availability checks without actually storing the data.

This is where “consensus” in a storage system needs careful language. When people hear dPoS, they often imagine block production and finality. In Walrus, the practical role is closer to selecting and securing the set of operators who must prove they are storing data, and then enforcing incentives around that obligation. The dPoS layer is doing Sybil resistance and accountability: it makes it hard to cheaply spin up fake capacity, and it gives the network a credible penalty lever when operators fail. Walrus’ own descriptions emphasize rewards for honest participation and slashing-style penalties for failing storage obligations, which is the economic spine you need if you want developers to treat “availability” as something more than marketing

The other side of the challenge is efficiency. A straightforward way to prevent data loss is brute-force backup: save full copies in many locations. It works, and it’s easy to explain, but it can get expensive quickly, especially when developers want to store real media, real game assets, real datasets, and they want to do it at product scale. In practice, the overhead you pay per stored byte becomes a product constraint. It shapes pricing, it shapes the kinds of apps that can exist, and it shapes whether “decentralized storage” remains a niche choice or becomes a default. Walrus’ Red Stuff design is explicitly aimed at reducing waste versus full replication while still supporting strong availability and self-healing recovery, because the system has to make economic sense, not just technical sense.

Retrieval performance is where storage ideals meet user impatience.

Slow writes are usually fine because they can happen in the background. Slow reads are not. If loading content feels choppy, the product feels broken. So storage systems are judged by one thing: can they bring data back quickly and reliably, like nothing interesting is happening at all

Redundancy helps durability, but it can also complicate reads if reconstruction is too expensive or too slow. Walrus’ approach tries to keep recovery bandwidth proportional to what was lost rather than forcing a full re-download of the entire blob during healing, which is the kind of detail that sounds academic until you are operating a real service during a messy week.

Walrus is also closely associated with the Sui ecosystem, and that anchoring can matter in practice without needing grand claims. Walrus uses Sui for coordination, attesting availability, and payments, and represents stored blobs as objects on Sui so smart contracts can reason about whether a blob is available, for how long, and under what conditions. This kind of integration can be a quiet developer-experience advantage: instead of stitching identity, payment, and storage logic across disconnected systems, teams can treat storage as something their onchain logic can reference directly. The best version of that story is not “magic composability,” it’s fewer moving parts for a product team that already has too many.

A grounded usage example looks almost boring: hosting media for an application that doesn’t want its user experience to depend on a single cloud bucket. Think long-form content, app media libraries, game patches, or datasets that need to be retrievable by many users over time

What you get is survival. A hosting outage or a policy shift shouldn’t wipe out your app’s data overnight. When storage is chosen for stability, not philosophy, builders focus on the right questions—and the product gets healthier because of it.

All of this still runs into the social reality of operational trust. Teams don’t migrate critical data because a whitepaper is elegant. They migrate when monitoring is sane, when failure alerts are actionable, when pricing is predictable enough to budget, when the tooling feels like it was built by people who have shipped systems, and when the community of operators looks stable rather than opportunistic. Delegated stake helps here in a subtle way: it creates reputational surface area. Operators want delegation, delegation wants uptime, and over time you get an ecosystem where “who is dependable” becomes legible. But that only works if the protocol is willing to enforce consequences, and if the developer experience makes it easy to treat those consequences as part of planning rather than as existential risk.

The balanced reality is that storage adoption is slow because switching costs are high and the cost of failure is brutal. You can multi-home compute. You can roll back deployments. You can patch a bug. But when you move data, you are moving the memory of the product, and you are betting that future retrieval will be as uneventful as past retrieval. Walrus’ wager, from what is publicly described, is that a dPoS-secured operator set, combined with erasure coding designed for churn and efficient recovery, can make decentralized blob storage feel boring enough to become a default assumption. If it succeeds, most users won’t know what Walrus is. Builders will notice it mainly when they realize they stopped worrying about where their large files live, because the system keeps returning them, quietly, day after day.