Tonight, Azu did something both stupid and typical in front of the computer. The boss asked Azu to help translate a cooperation agreement from two years ago, saying there was a clause that needed to be reviewed. I opened the company cloud drive and clicked through 'Client Information - Signed - Archived - 2024', only to be greeted by a whole graveyard of file names: 'Final Version_v3.pdf', 'Final Version_Ultimate Version.pdf', 'Boss Revised.pdf'. While downloading, I cursed inwardly: Two years have passed, who can still remember which version was the one actually executed? Even more fantastical is that even if I throw this 'correct version' of the contract into IPFS, attaching a hash on the chain, the block explorer will only coldly give me a string of hexadecimal characters. The chain can't understand the clauses, AI can't understand the semantics, and apart from 'proving it existed', no one truly understands this document. At that moment, I suddenly realized: in the eyes of most systems today, 'documents' are essentially cold corpses - packed into cloud drives, bundled into hashes, tossed into some corner of a node, only to be dug up from the grave when we search on our knees.

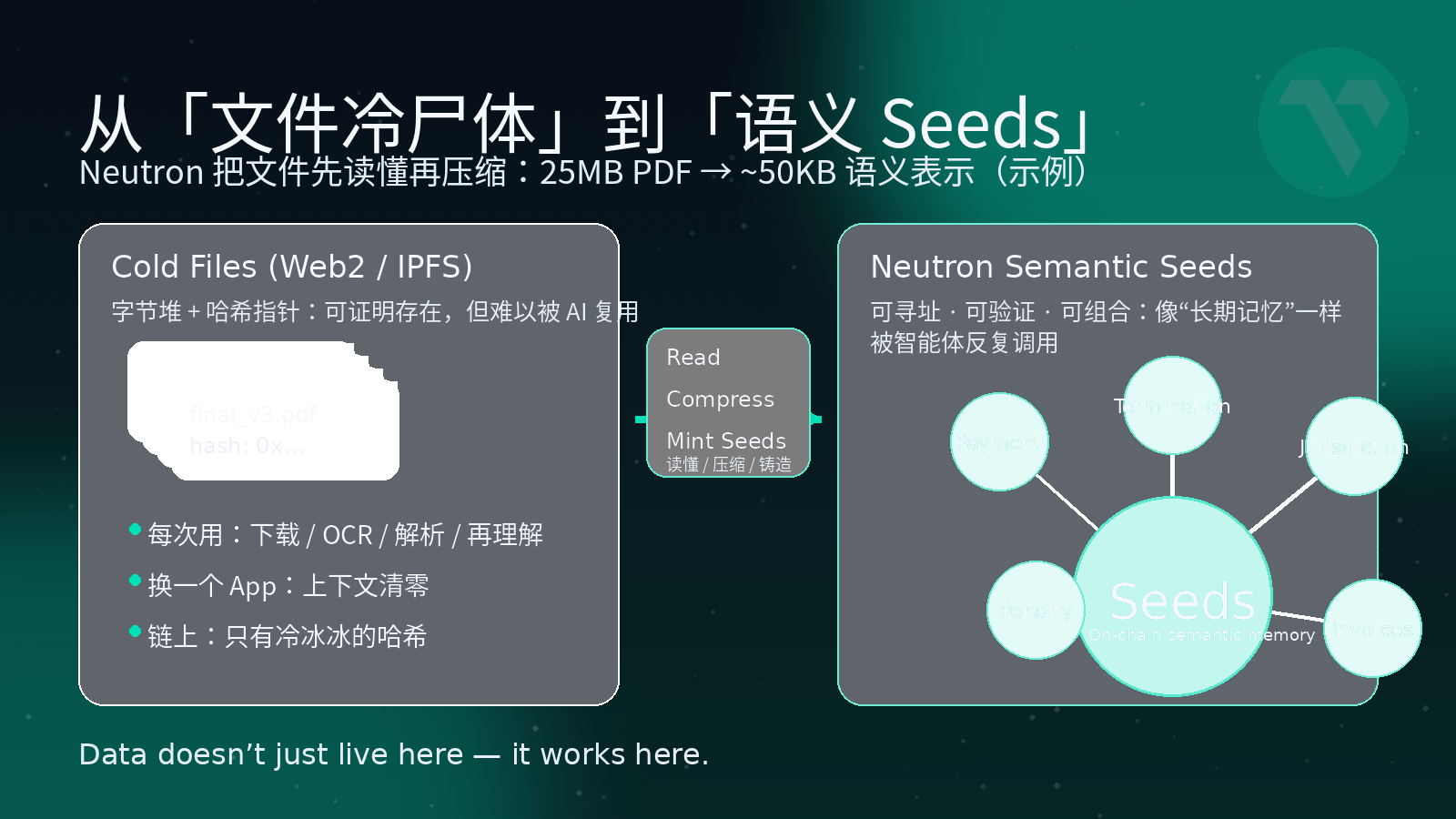

The problem is, we often talk about the 'AI era' nowadays. If data is still treated like a corpse, then the so-called AI on-chain and Agent economy, to put it bluntly, is often just about giving the cold corpse a fancier coffin. The underlying assumption of traditional storage is particularly simple and crude: files are just a pile of bytes. The work of cloud storage is to help you keep this pile of bytes a bit farther away and make a few copies; public chains are even easier, directly tossing files to IPFS, leaving only a hash on-chain, and pairing it with a gateway. In the Web2 era, this could still work because it was people who truly understood the content of the files—contracts needed lawyers to review, audit reports needed accountants to check, and operational reports required operations to export to Excel and then create pivot tables. But in the AI era, this logic has reversed: those who really need to 'understand the files' are no longer just people, but an entire group of intelligent agents online 24/7.

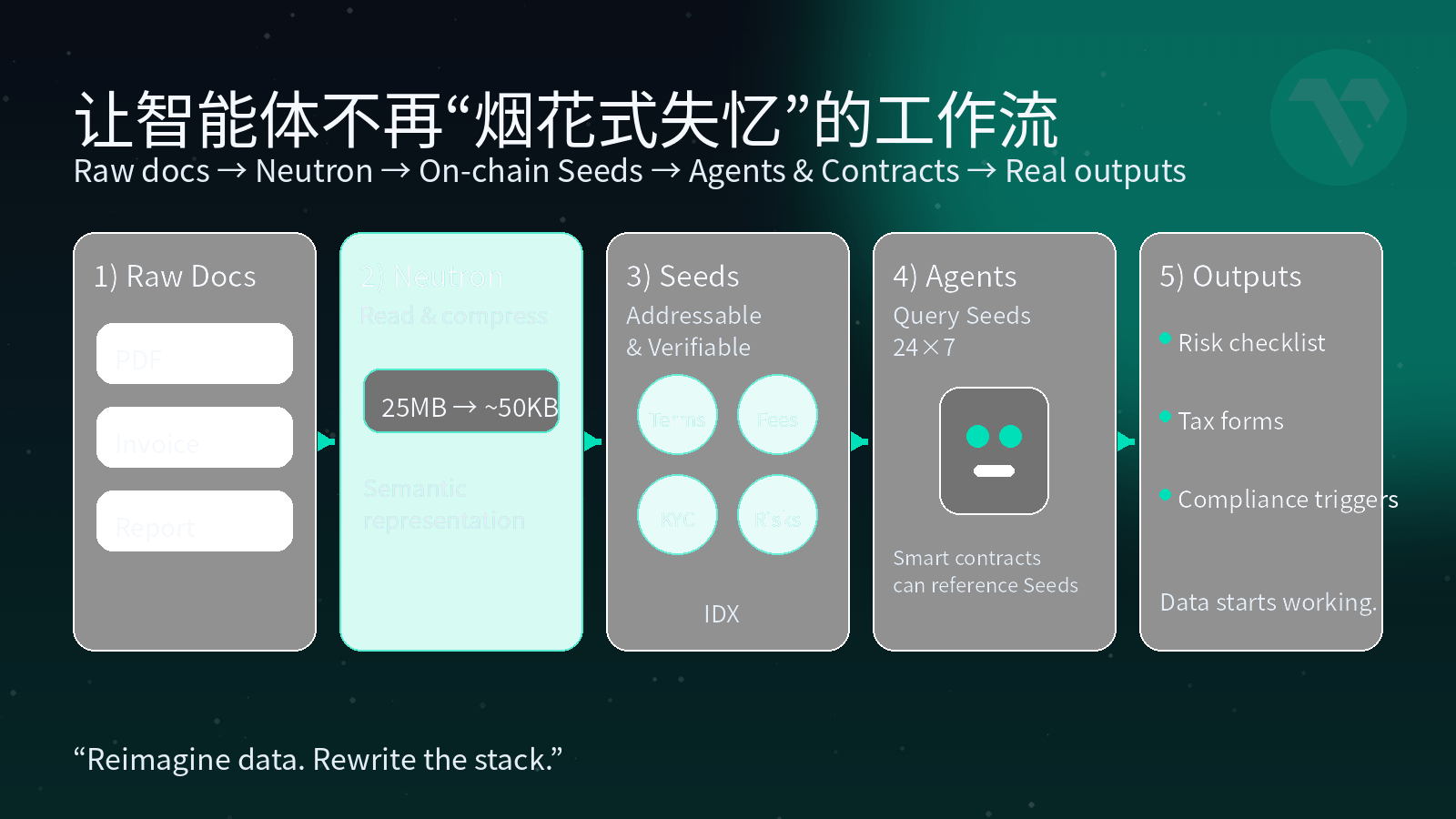

Imagine your AI assistant helping you with a few very normal tasks: automatically extracting all 'termination clauses' from historical contracts to create a risk list; helping you translate a complete set of real estate transaction documents, identifying tax and compliance risks; remembering all your invoices, flight tickets, and hotel bookings from the past year, automatically organizing them into tax forms during tax season. If these items are just lying in 'cold files', the AI has to download, reparse, and re-understand them every time it needs to use them. Switching to another product means all memory is wasted and starts over. In this mode, data is treated as a 'one-time input' rather than 'long-term reusable memory'. This is the Achilles' heel of most so-called 'AI applications': the model appears intelligent, but it lacks a semantic memory layer that can be relied upon long-term.

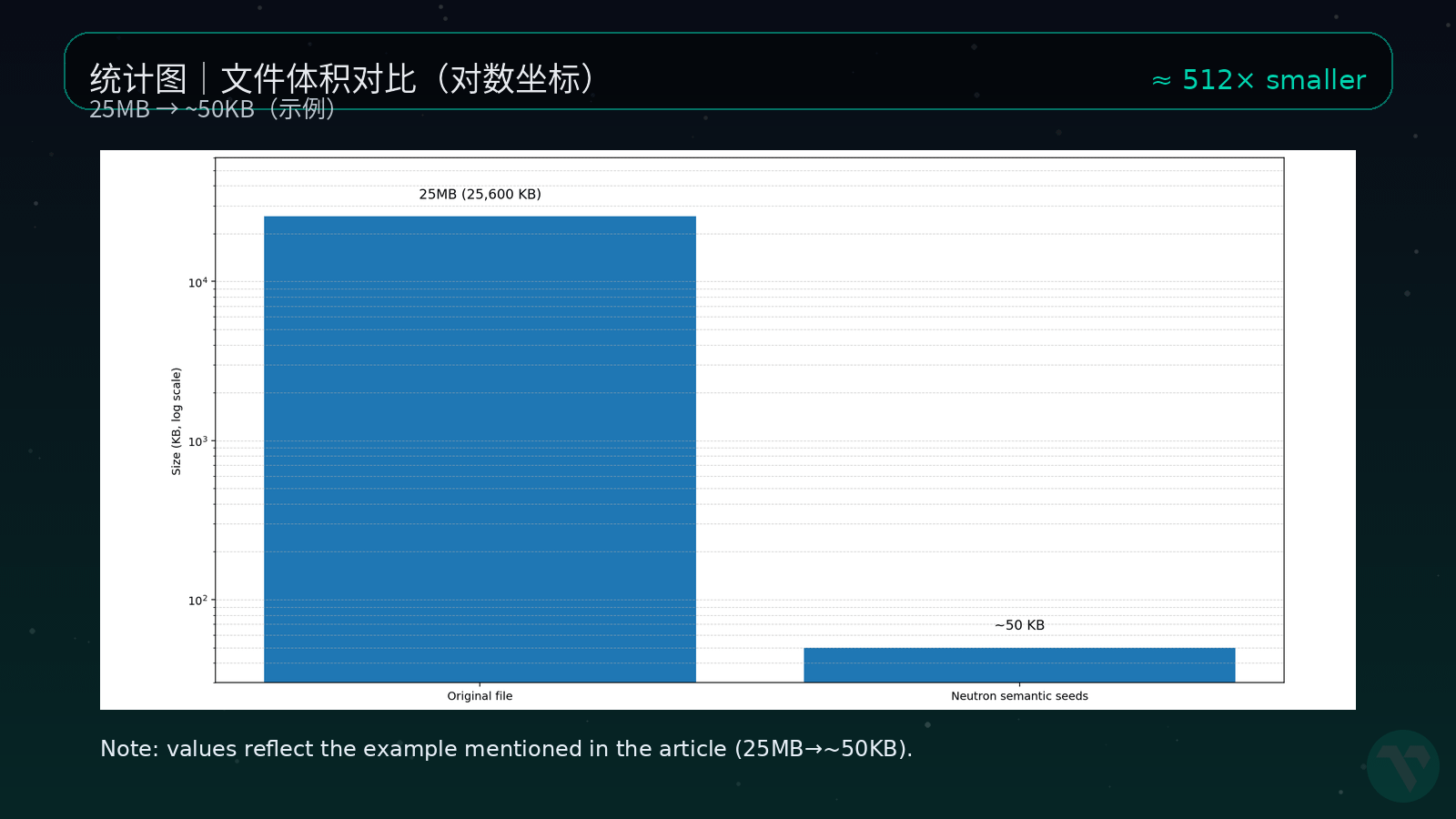

Vanar's answer is called Neutron. It straightforwardly does not position itself as 'another storage solution', but very directly states: this is a Semantic Memory Layer—semantic memory layer. In layman's terms, Neutron does two things. The first step is to 'understand' the file and then compress it. It does not simply zip up a PDF, but first uses semantic and heuristic methods to cut the original file into meaningful segments, then reconstructs it into a new representation; it compresses 'information redundancy' and 'expression form', not the content itself. You give it a 25MB PDF, and after understanding the content, it can compress the core semantics into a representation of about 50KB, while keeping your information, context, and structure intact. The second step is to forge this understanding into individual Seeds—'knowledge seeds' that can be understood by AI and referenced by contracts. Neutron no longer treats files as a blob, but breaks them into many Seeds, each of which is an independent, addressable, verifiable semantic unit, and is directly on-chain, rather than a half-baked solution of 'off-chain storing files + on-chain placing pointers'.

In the world of Neutron, files are no longer just 'a link' or 'a hash', but an entire piece of semantic land that can be seeded by AI and repeatedly harvested by application layers. You can think of Seeds as the 'soul of the file': the physical body has changed countless times during uploads and migrations, but what is carved on these Seeds is what the file truly wants to express, and it can be shared and used by different intelligent agents. A file that was originally 25MB can be compressed into a collection of Seeds just a few tens of KB in size, all of which are put on-chain, becoming a long-term memory that can be indexed, proven, and combined.

At that point, many originally painful scenarios will undergo significant phase changes. For example, that 25MB legal contract mentioned earlier, after entering Neutron, will be split into multiple Seeds: one corresponding to all 'breach of contract' clauses, another for 'payment conditions', and another carrying 'applicable laws and dispute resolution mechanisms'. When an intelligent agent in the Vanar ecosystem wants to ask: 'Help me find all contracts in a specific jurisdiction with arbitration clauses and breach penalties exceeding X, and estimate how much I would owe if I breach.' It no longer needs to download the original PDF and scan through it violently; it can run queries directly on the Seeds on-chain. For AI, the chain is no longer a 'ledger', but has truly become a 'searchable legal knowledge base'.

For example, invoices and reports. You give Neutron all your invoices, flight tickets, and hotel bookings from the year, and it will compress these invoices into a string of semantically grouped Seeds: amounts, tax rates, categories, and suppliers are all structured. When tax season arrives, you only need to tell your AI: 'Help me calculate how much tax I can deduct this year and export it according to the tax bureau's template.' The agent no longer starts from OCR on jpg and pdf, but directly performs calculations based on Seeds. Those messy receipts scattered in your email and cloud storage become, for the first time, 'self-working assets'.

Interestingly, Seeds are not a private format of any app, but a public language of the entire Vanar stack. A knowledge Seed generated in myNeutron can be read and invoked directly by other Vanar ecosystem applications and even reasoning engines like Kayon; memory no longer belongs to a specific application, but to you and this chain. Vanar's slogan, 'Reimagine data. Rewrite the stack.', is reflected here: data is no longer just passively 'alive', but has truly started to 'work'. Before Neutron, the vast majority of data on the chain was dead accounts, individual transactions, and hashes; after Neutron, files compressed into Seeds will continuously provide context for AI and contracts, rather than quietly lying in cold storage gathering dust.

From an architectural perspective, Vanar places Neutron in a very subtle yet crucial position: the underlying layer is responsible for execution and settlement (L1), the upper layer has Kayon which specializes in reasoning and can directly read Seeds for on-chain reasoning, while the middle layer Neutron is specifically responsible for transforming files from the real world into 'semantic memory' that AI can understand and contracts can call upon. Most people discussing 'AI public chains' are still focused on competing for TPS, transaction fees, and whether or not to include native large models, but teams that are truly running products will gradually realize: if you cannot solve the problems of 'memory' and 'data semanticization', all Agents and automation will eventually degrade into one-time fireworks—chatting with you today, completely forgetting who you are tomorrow, and when you switch to another product next week, the previous context will be rendered invalid.

What Neutron does sounds not sexy at all: it doesn’t focus on 'ten times TPS', nor does it shout 'the largest global ecosystem', but quietly rewrites the notion that 'files are cold corpses' into 'files are thinking, programmable Seeds'. In Azu's view, this seemingly inconspicuous 'compression screw' may very well determine a big issue: whether the chain of the AI era continues to be a high-end version of a ledger or truly possesses its own long-term memory for the first time. By 2026, when someone actually starts throwing Agents on-chain to manage assets and run workflows, you will find that computational power can be rented, models can be changed, and even L1 can be migrated, but that entire piece of long-term memory compressed into Seeds is the one thing that any intelligent agent system would be most reluctant to part with.

So while the market is still focused on who has higher TPS, who has created a new model, or who is shouting louder on social media today, I am more willing to spend time focusing on these small components buried in the middle layer. Because history has repeatedly proven: those who truly change the game rules are often not the ones holding the microphone on stage, but the engineers tightening the screws one by one behind the scenes. In the story of Vanar, Neutron is that little screw that 'compresses a 25MB file into 50KB thinking Seeds'—it doesn’t steal the spotlight, but it determines whether the entire AI stack can stand firm in the long term.