To survive in decentralized storage, it's never about how well the 'story is told', but whether the ledger can be self-consistent. You can have on-chain 'receipts' like PoA, and coding projects like Red Stuff that reduce costs, but if the token model cannot support 'long-term service', the network will ultimately slide into one of two outcomes—either it relies on subsidies to hold on until resources run out, or it drives users away by raising prices. So we specifically talk about $WAL: it is not just decoration, nor is it born for the K-line of exchanges; it is the payment layer, security layer, and governance layer that Walrus uses to turn 'data services' into a long-term business.

Let's start with payment. In the official definition, WAL is Walrus' storage payment token, but there is a very critical design here: the official statement clearly says that the payment mechanism is designed to keep storage costs stable in fiat terms and 'hedge against long-term price fluctuations of WAL'. Users purchase storage based on 'fixed time' pre-payments, and the pre-paid WAL will be distributed over time to storage nodes and stakers as compensation for their continued service. This logic is very similar to paying for a year's cloud service: you do not pay daily, but sign the contract in one go, and the service provider then realizes income over time. It does not solve 'how to be cheaper', but 'how to make users willing to use, nodes willing to invest, and the network willing to commit long-term'.

Moreover, Walrus clearly acknowledges: the chicken-and-egg problem of early networks must be broken with 'seed funding'. Therefore, in the distribution of WAL, the official statement clearly allocates 10% of Subsidies, aimed at promoting adoption in the early stages: allowing users to access storage at a cost lower than market prices, while ensuring that nodes can run a commercial model. This statement is very 'realistic': if you immediately go fully market-oriented, with large price fluctuations and long payback periods for nodes, in the end, only a very small number of people willing to 'generate power with love' will remain—that's not infrastructure, but a community.

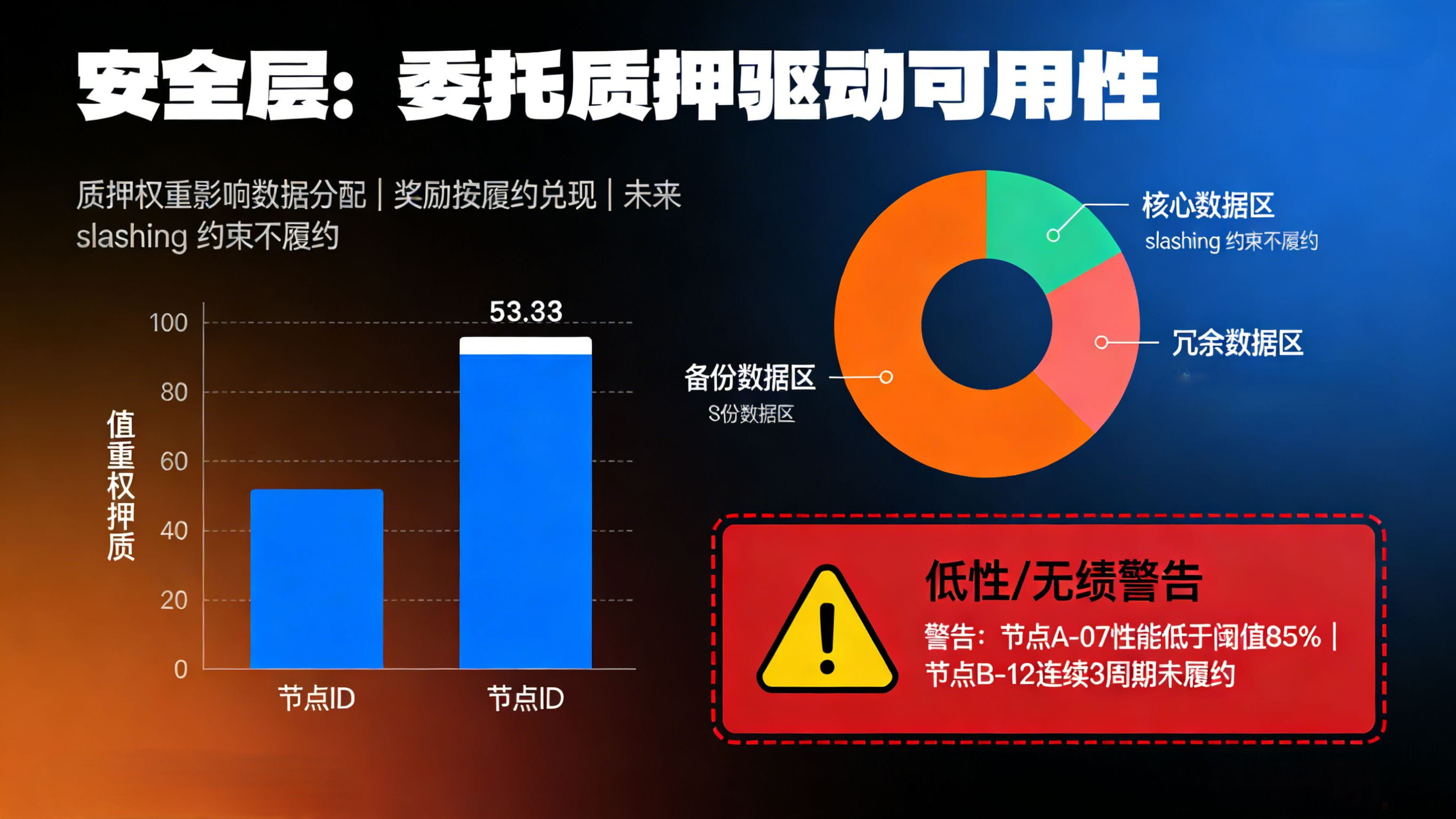

Next, let's talk about security. Many people think that the security of storage networks relies only on 'technology', but Walrus' statement is very direct: the security of Walrus is supported by delegated staking (Delegated Staking). Anyone can stake WAL to participate in network security, and it is not necessary to operate a node themselves; nodes will compete to attract delegated staking, and 'staking weight' will affect how data is distributed to which nodes; nodes and their delegators will earn rewards based on performance. You can think of it as a 'verifiable service performance contract': nodes do not claim they are reliable just by words, but by continuously fulfilling obligations, staying online, and being available to earn rewards; users are not blindly staking, but are staking on 'who can deliver the service better'.

More importantly, Walrus has repeatedly stated in various official materials that 'penalties' are a key element for aligning incentives in the future: the economic framework of the PoA mechanism clearly states that the network adopts dPoS, and nodes will earn rewards for honest participation. Additionally, when penalties (slashing) are implemented, they will face financial penalties for failing to fulfill storage obligations. The token page also emphasizes: once slashing is enabled, these mechanisms will align the interests of WAL holders, Walrus users, and node operators 'completely'. This statement translates into plain language: if you don't serve, you'll lose money; if you serve well, you deserve to earn profits.

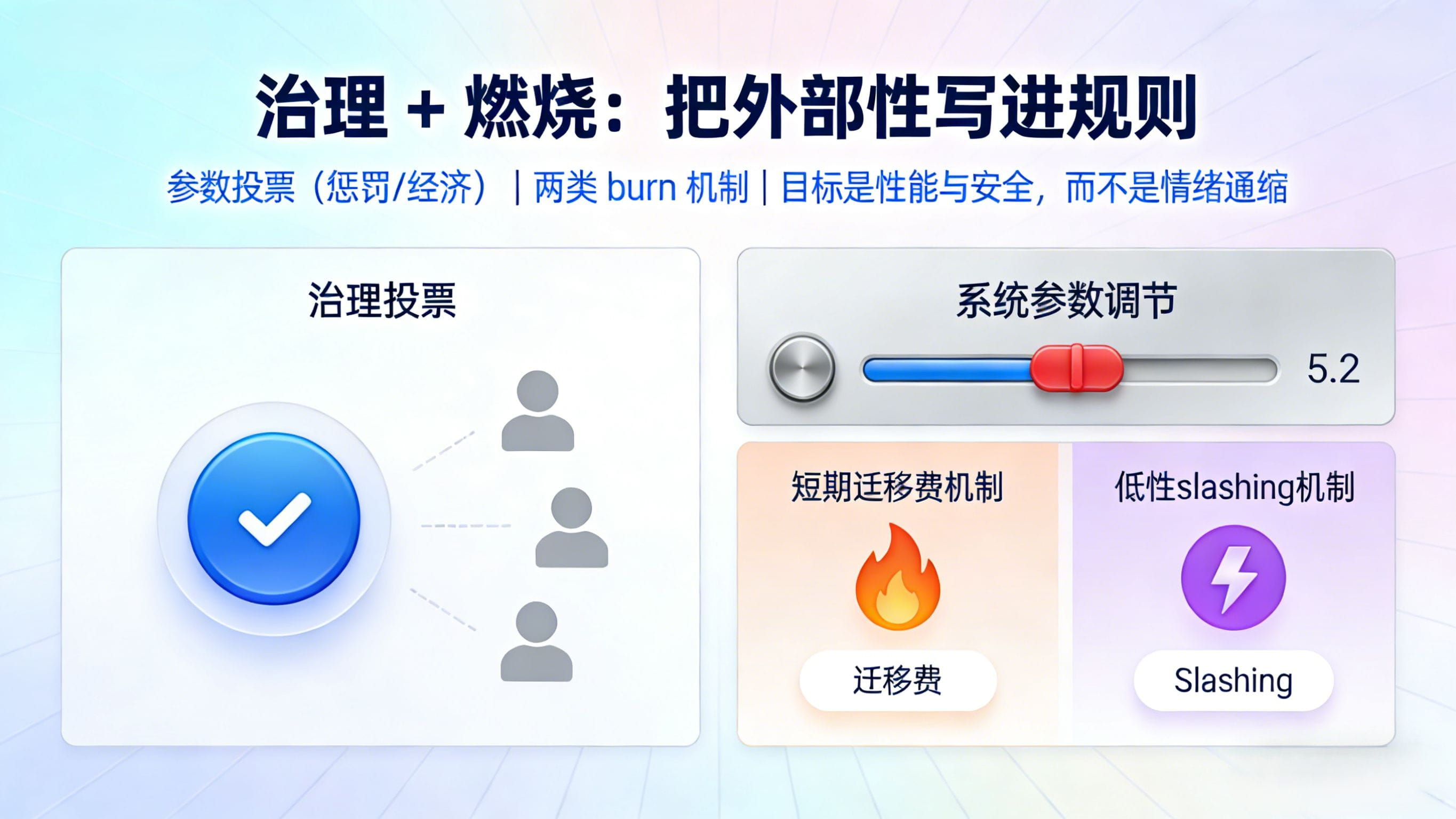

Next, let's talk about governance. Many projects' 'governance' is just for show, but Walrus' governance goals are very focused: adjusting system parameters, especially penalty levels and economic parameters. The official statement is clear: governance operates through WAL, and nodes will vote based on their respective WAL staking weight to determine various penalty levels; because nodes often bear the costs arising from other nodes' 'poor performance', they are responsible for calibrating financial consequences. This is very similar to an industry association: those truly harmed by externalities care the most about setting reasonable rules—penalties that are too light scare no one, while penalties that are too heavy discourage supply.

Then comes the part you care about the most, which is also the easiest to be turned into a slogan: burning. The ancestors made the conclusion clear: Walrus' 'burning' is not to create a deflationary sentiment, but to solve engineering problems. The official statement clearly states that WAL will introduce two types of burning mechanisms, emphasizing that 'after implementation' there will be deflationary pressure on the tokens, but the goal is still to serve network performance and security models. You see, it puts 'deflation' at the back and 'performance and security' at the front; this order is correct.

The first type of burning targets 'short-term staking migration noise'. The official statement is very specific: short-term stake shifts will incur a penalty fee, part of which is burned, and part is distributed to long-term stakers; the reason is not a moral critique, but an economic externality—frequent migration forces data to move between nodes, leading to expensive migration costs. So this is not 'punishment for speculation', but 'returning the costs you create back to the system', while encouraging longer-term security commitments.

The second type of burning targets 'low-performance nodes'. The official statement says: staking to low-performing nodes will trigger slashing, and a portion of the fees will be burned; the significance of slashing is to make long-term stakers more willing to vote for truly reliable nodes, while also preventing malicious parties from exploiting the system. This type of burning is essentially a 'quality filter': it strips profits from the slackers, forcing the entire network to converge towards higher availability and reliability.

Putting payment, staking, security, governance, and burning together, you will find that the logic of WAL is actually very 'infrastructure': users use it to buy certainty (pre-payment, fiat stable metrics, cross-time distribution); nodes use it as collateral (staking participation, striving for delegation, exchanging performance for rewards); the network uses it for constraints (future slashing and penalties); the community uses it to adjust parameters (governance decides penalties and economic allocation); and burning writes the real costs of 'noise and low performance' into the system rules.

Finally, I give you a 'checklist for understanding WAL', so that in the future, when you look at any infrastructure tokens, you can ask these questions:

First, is there real payment demand? Walrus clarifies: WAL is used for storage payments, designed to be more stable in fiat terms, with pre-payments distributed over time.

Second, is there a demand for secure staking? Walrus clarifies: delegated staking supports security, nodes compete for staking which affects data distribution, and future slashing aligns obligations.

Third, can governance change key parameters? Walrus clarifies: governance adjusts system parameters and penalty levels, voting according to WAL staking weight.

Fourth, do penalties/burning serve network performance? Walrus clarifies: short-term migration penalties and part of low-performance slashing burning are meant to suppress migration costs and filter node quality.

If you can answer these four questions clearly, then looking at WAL will not be just about 'price', but will truly show how a data infrastructure writes 'service commitments' into the economic system. I also want to hear your honest opinion in the comments: do you think the most market-valuable aspect of WAL is 'payment demand', or 'the long-term reliability premium brought by security staking and penalty mechanisms'?