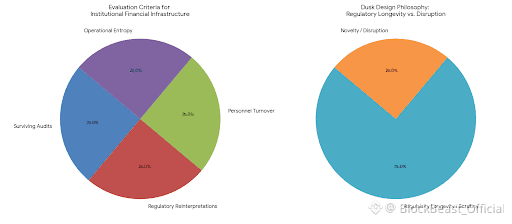

When I look at projects like Dusk, I tend to evaluate them less as “blockchains” in the abstract and more as attempts to build financial infrastructure under real institutional constraints. That framing matters. Financial systems are not judged by novelty or elegance alone; they are judged by whether they can survive audits, regulatory reinterpretations, personnel turnover, and years of operational entropy. From that perspective, Dusk’s design choices read less like a bid for disruption and more like an effort to make something that could plausibly be deployed by actors who already operate under scrutiny.

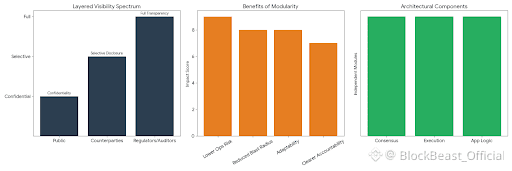

The emphasis on regulated, privacy-aware financial use cases immediately narrows the design space. In traditional finance, privacy is rarely absolute. Banks, custodians, and market operators live in a world of layered visibility: confidentiality toward the public, selective disclosure toward counterparties, and full transparency toward regulators and auditors under defined conditions. Dusk’s approach to privacy aligns more closely with this reality than with the absolutist narratives that dominated early crypto discourse. Privacy here is treated as a configurable property—something to be scoped, permissioned, and revealed when required—rather than as an ideological end state. That choice sacrifices some rhetorical appeal, but it reflects how compliance actually functions in practice.

The architectural emphasis on modularity follows a similar logic. Separating consensus, execution, and application logic is not a flashy move; it is a conservative one. In regulated environments, change is expensive. A system that allows components to evolve independently reduces the blast radius of upgrades and lowers the operational risk of adapting to new requirements, whether they come from regulation, market structure, or internal governance. Modular design also creates clearer accountability boundaries—something that matters when external auditors or regulators ask not just what a system does, but who is responsible for each part of it.

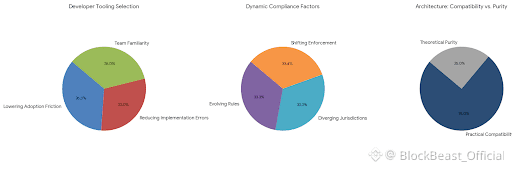

Compatibility with existing developer tools and paradigms fits into this same pattern of restraint. Financial institutions are rarely willing to retrain teams or rewrite systems unless the benefits are overwhelming. Choosing familiar tooling, even if it limits certain design freedoms, lowers adoption friction and reduces the likelihood of subtle implementation errors. In production finance, the cost of a misunderstood abstraction often outweighs the benefits of a more theoretically pure model.

The separation of privacy mechanisms from core settlement logic is another example of deliberate risk management. By treating privacy features as composable layers rather than monolithic assumptions, the system leaves room for different disclosure regimes and regulatory interpretations over time. This is important because compliance is not static. Rules evolve, jurisdictions diverge, and enforcement priorities shift. A system that hard-codes a single view of “acceptable privacy” risks obsolescence when those external conditions change.

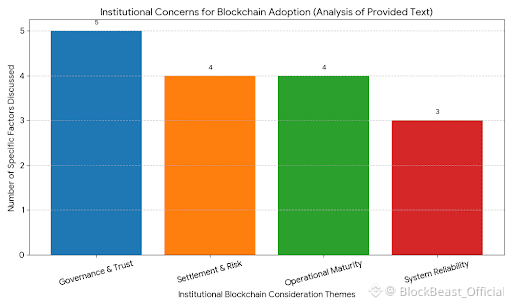

None of this removes practical limitations. Settlement latency, for instance, is not just a technical metric; it affects capital efficiency, liquidity management, and intraday risk. In institutional contexts, slower settlement can be acceptable, but only if it is predictable and well understood. Similarly, any reliance on bridges, migrations, or external trust assumptions introduces governance questions that cannot be hand-waved away. Who controls upgrades? Under what conditions can assets be frozen, migrated, or unwound? These are not edge cases—they are central to whether regulated entities can justify participation.

Operational details often reveal more about a project’s maturity than its whitepaper. Node upgrade processes, backward compatibility guarantees, documentation quality, and the cadence of releases all determine whether an infrastructure can be maintained by real teams with limited tolerance for surprise. In my experience, systems fail less often because of missing features than because of unclear procedures during routine operations. A network that behaves predictably under stress, even if it is slower or more constrained, is usually preferable to one that promises flexibility but delivers ambiguity.

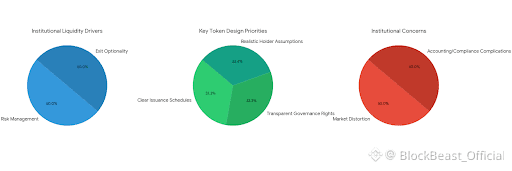

Token design, viewed through an institutional lens, is similarly unromantic. Liquidity matters not for speculation, but for risk management and exit optionality. Clear issuance schedules, transparent governance rights, and realistic assumptions about who will hold the token—and why—are more important than incentive schemes designed to drive short-term activity. Institutions care about whether they can enter and exit positions without distorting markets, and whether token mechanics introduce accounting or compliance complications downstream.

Taken together, Dusk reads as infrastructure shaped by an awareness of how financial systems are actually used and overseen. Its choices suggest a willingness to accept constraints in exchange for durability. That does not guarantee success; no design can fully anticipate regulatory shifts or market behavior. But there is value in building systems that assume scrutiny rather than resist it, and that prioritize clarity over cleverness.

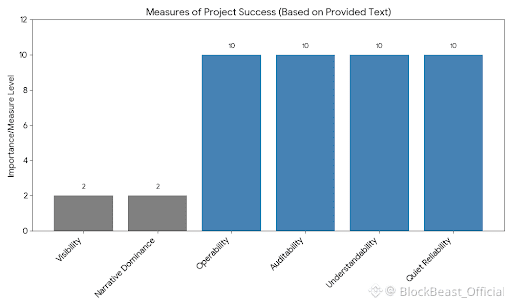

In the end, the measure of such a project will not be visibility or narrative dominance. It will be whether, years from now, it can still be operated, audited, and understood by people who were not there at its inception. In regulated finance, quiet reliability is not a marketing slogan—it is the baseline requirement. Systems that internalize that truth early tend to last longer than those that discover it only after something breaks.